Fact Sheet

Stroke

Who this is for:

A stroke, disrupted circulation that kills brain tissue, can leave neurological impairments including paralysis, partial or total loss of language, and severe cognitive deficits. There are roughly 800,000 strokes yearly in the United States—one every 40 seconds. It is the fifth leading cause of death in this country, and second worldwide.

Although strokes are sudden, the brain injury they inflict typically evolves over the course of hours, or even days. Prompt, effective treatment can mean the difference between a good recovery and disability or death.

What is a Stroke?

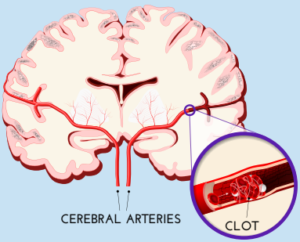

Ischemic strokes, which occur when blood flow to part of the brain is blocked by a clot, are most common, accounting for 87 percent of the total.

The clot may originate in the heart (known as cardioembolic stroke), often due to disturbed heart rhythm, and travel through the bloodstream to lodge in a cerebral artery. Or, a clot may break off from a plaque of fatty material lining an artery (atherosclerosis) within or outside the brain. Atherosclerosis can also narrow brain arteries, making them more vulnerable to blockage.

The effects of stroke depend on where in the brain blockage occurs and the size of the blocked artery. A clot on one side of the brain is likely to cause weakness, paralysis, or sensory loss on the opposite side of the body. If on the left side of the brain, the stroke may impair speech; on the right, vision and hearing. Memory loss often follows a stroke on either side. With the blockage of an artery supplying the back of the brain, dizziness and loss of balance, difficulty swallowing, and heart and breathing disturbances are common.

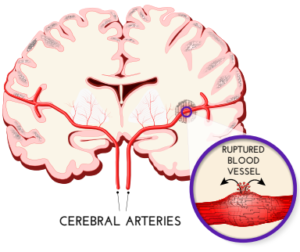

Hemorrhagic strokes are often more severe. A ruptured blood vessel bleeds directly into the brain (intracerebral hemorrhage) or into the space between the brain and skull (subarachnoid hemorrhage).

In most intracerebral hemorrhages, the artery has been weakened or damaged by chronic high blood pressure. The usual cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage is an aneurysm—a bulging or ballooning weak spot in the artery wall.

Because hemorrhagic strokes often affect large areas of the brain, their consequences are frequently extensive and worsen rapidly.

The Ischemic Cascade

Brain injury from an ischemic stroke involves a complex molecular process.

Without enough glucose and oxygen for energy, the neuron cannot maintain chemical equilibrium, and excessive calcium and sodium enter the cell body. This triggers the release of excitatory neurotransmitters, which allows even more positive ions in, activating proteolytic enzymes (responsible for breaking down proteins) and inflammatory chemicals. Swelling with water, brain cells deteriorate and die.

Disruptions in the function of mitochondria, energy-producing parts of the cell, and breakdown in the blood-brain barrier also play a central role.

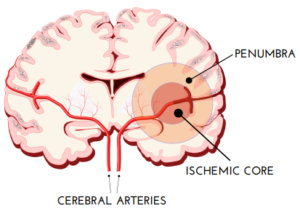

Neurons in the area where blood supply is cut off nearly completely (the ischemic core) succumb in minutes. But in a broader zone of moderately impaired circulation (the penumbra), they may survive for days, returning to normal if blood supply is restored quickly enough.

Hemorrhagic Stroke Damage

Blood from ruptured vessels irritates the brain, causing the initial symptoms of intracerebral hemorrhage. As the mass of blood (hematoma) grows, increasing pressure damages brain tissue. In a subarachnoid hemorrhage, blood trapped between the brain and the inelastic skull exerts similar pressure.

Processes set in motion by hemorrhage aggravate the injury in subsequent hours and days. The chemical thrombin, produced by the body to form clots and stop the bleeding, is toxic in large quantities. It promotes edema, tissue swelling that raises pressure further. Red blood cells within the hematoma break down and release iron, worsening edema and injuring brain cells by oxidation.

Inflammation adds to the damage. Blood components activate immune cells in brain tissue (microglia) and leukocytes (white blood cells) from the bloodstream, releasing chemicals that promote edema and disrupt the blood-brain barrier.

The pressure of the hematoma and edema can trigger vasospasm, blood vessel constriction that causes ischemia in the brain weeks later.

Acute Treatment

Time is of the essence. Stroke symptoms demand immediate medical attention.

KNOW THE WARNING SIGNS

Prompt treatment can save lives, prevent disability, and preserve memory. Time lost is brain lost: An average of one million brain cells (out of 100 billion) die every minute of delay.

Call 911 immediately if you see or experience:

- Drooping, numbness, or paralysis of the face

- Weakness or numbness on one side of the body—particularly an arm or leg

- Slurred speech or difficulty in speaking or understanding speech

- Confusion, dizziness, difficulty walking due to impaired balance or coordination

- Sudden, severe headache

- Double vision or other difficulty with sight

Ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes have similar symptoms but require very different treatment, and the first necessity is distinguishing between them by CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

During an ischemic stroke, restoring blood flow rapidly can prevent permanent brain damage within the penumbra and even revive cells in the ischemic core, preserving brain function. A drug to dissolve the clot, intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), is most effective when given within three hours of first symptoms, but there are still substantial benefits within up to four-and-a-half hours.

tPA administered directly to the brain through an artery may still be helpful six hours after the stroke begins—for some strokes in the back of the brain, there is some evidence of effectiveness 12 or 24 hours later.

For clots in larger arteries, physical removal (mechanical thrombectomy) has become an important option. A catheter is threaded through an artery up from the groin, and the clot is either grabbed with a stent—a tiny mesh tube— or sucked out. This is ideally done within 6 hours, but up 24 hours after symptoms begin, physical removal of the clot may still limit brain injury.

Immediate treatment of a hemorrhagic stroke centers on keeping blood pressure down. Medication or surgery may also be used to reduce the pressure of edema and accumulated blood on the brain, and a calcium channel blocker (a drug to relax the arteries) may be added to prevent vasospasm.

For a person taking an anticoagulant—a clot-inhibiting drug such as Coumadin (warfarin), Eliquis (apixaban), or Pradaxa (dabigatran)—treatment includes a drug to rapidly halt its action.

Are You at High Risk?

While anyone can have a stroke, certain factors increase the danger:

- Age: The older you are, the more likely you are to have a stroke. But younger people are not immune: 38 percent of strokes occur before age 65.

- Race: Non-Hispanic Black adults are 50 percent more likely to have a stroke than white adults. The risk is particularly high for Black women.

- Illness: High blood pressure is a major risk factor for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Atrial fibrillation, a kind of irregular heartbeat, can produce blood clots that cause stroke. Heart disease and diabetes damage the artery lining, greatly increasing risk. People with late-life epilepsy and migraines with aura have more strokes. A new risk is Covid-19: Several studies have found increased strokes within nine months after infection.

Special Alert: In a transient ischemic attack (TIA), often called a “mini-stroke” or “minor stroke,” a small clot blocks a blood vessel and dissolves or dislodges spontaneously and flows away, It causes the same symptoms as stroke, but typically lasts five minutes or less, although it may persist as long as a day. No matter how brief, a TIA should not be ignored—it’s a warning that a real stroke may be imminent. Get medical attention without delay. Similarly, if you’ve had a stroke, you’re in danger of another—nearly one stroke in four occurs in those who have already had one.

Protect Your Brain

Eighty percent of strokes can be prevented. These lifestyle adjustments and medical safeguards are important for everyone, but especially if you are an increased risk:

- Correcting high blood pressure, which affects nearly one-half of Americans, should be a top priority. Reduce it (to 120/80mmHg) with a low-salt diet, a healthy lifestyle that includes exercise and weight control, and medication, if necessary.

- Stop smoking.

- Avoid alcohol in excess (more than one drink daily for women, two for men).

- The same measures that reduce heart attack risk protect against stroke as well: control weight and cholesterol by eating well (such as the vegetable-based Mediterranean diet), taking medication if necessary, and exercising regularly.

- Talk to your doctor about atrial fibrillation (AFib), a common heart rhythm disturbance that triples ischemic stroke risk unless treated with an anticoagulant drug to keep clots from forming.

- If you’ve had a TIA or prior stroke, you may need clot-preventing medication too.