Impact Story

Beyond the Basics in Science Education

NeuroSociety Stories with Jayatri Das

In 2022, the Dana Foundation awarded a grant to The Franklin Institute (TFI) to update their Neuroscience & Society Curriculum for high school students to include an in-depth focus on neuroscience through the lens of relevant societal issues. The original curriculum, published in 2017, had become outdated after events such as the global Covid-19 pandemic and rapid developments in certain technologies. It was clear “neuroscience was advancing in ways that weren’t represented in the prior curriculum,” said Jayatri Das who is chief bioscientist at The Franklin Institute and oversees the project.

Das ensured the new curriculum incorporated central themes such as the relationships between the brain and mental health, and the areas of life that will be transformed by neuroscience in the near future. Learn more about Jayatri’s background as an educator and best practices for effective public engagement in science in this episode of “NeuroSociety Stories.”

Read about our “NeuroSociety Stories” series and find bonus footage here. And be sure to check out the curriculum, which is available for free on The Franklin Institute’s website.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

CAROLINE MONTOJO, HOST: Hello, and thank you for joining “NeuroSociety Stories.” These conversations are an opportunity to share stories about neuroscience and society. These can come from Dana grantees, partners, and others who seek to increase neuroscience’s impact on society. I’m Caroline Montojo, president and CEO of the Dana Foundation. Our mission is to advance neuroscience that benefits society and reflects the aspirations of all people. We’re supporting work to understand how neuroscience can shape a brighter future by fostering meaningful connections between scientists and other scholars, and the people whose lives could be impacted by their work. Today, we are delighted to have Jayatri Das join us in a discussion on public engagement in science. This engagement can take place in K-12 education and also in lifelong learning outside of school. Jayatri Das is chief bioscientist of Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute. There, she led the development of the award-winning exhibit about neuroscience and psychology. Jayatri, welcome. Thank you for joining us today.

JAYATRI DAS: Thanks so much for having me, Caroline.

MONTOJO: Absolutely. To start us off, can you tell us about your work at The Franklin Institute and your background?

DAS: So, I’m actually an evolutionary biologist by training. I come into neuroscience from a little bit of a different angle. As I was finishing my Ph.D., there was a really highly publicized trial about teaching evolution in Pennsylvania just a few hours away from where I grew up. All of the coverage around that trial really brought into focus for me the bigger issues in science education, especially when we think about evolution, about how people’s values and personal experience really shape their understanding and, really, perception of the value of science. And that really comes into perspective with evolution, in particular, but certainly many other areas of science.

MONTOJO: I’d also love to hear what inspired your career path into science public engagement.

DAS: I was lucky enough to find a fellowship in a science museum that gave me a window into the professional world of museums, and that was really eye-opening for me. I always went to science museums as a kid but didn’t really realize who worked there. And realizing that combination of working with public audiences when they’re really self-driven to learn, that was so exciting. They’re bringing their knowledge—their understanding—to this space, and then the creativity that science museums bring to making experiences that foster that learning, that was a combination that had me hooked.

MONTOJO: Jayatri, how did you first get involved with neuroscience? You mentioned evolutionary biology as your training.

DAS: Before I was hired at The Franklin Institute, TFI was planning to expand the building and create a whole new signature exhibition, and they had surveyed the audience to find out what people were interested in, and the choices that they surveyed were: the brain, the cell, and Benjamin Franklin. And, thankfully, it was a community who voted for the brain because what a rich opportunity to explore an emerging field of science that really shapes our lives every day, and it’s just expanded in directions I could never have predicted.

MONTOJO: Can you share what discussion and critical thinking skills are needed to be able to go beyond the basic neuroscience topics, to exploring these topics in science and society?

DAS: Knowledge about science is only part of the picture. What do you do with that knowledge, and how do you feel empowered to apply that knowledge in your everyday lives? Obviously, there’s foundational neuroscience that we want students to learn because that really helps our understanding of the world. But beyond that, it’s really thinking about, “How do I have dialogue with somebody where I’m open to learning somebody else’s perspective and maybe willing to change my mind?” And, so, we really think about structuring those skills in kind of four different ways. In addition to learning science knowledge, we want to encourage skills of asking questions, making connections, cultivating that scientific thinking, and then really just encouraging that dialogue between different people.

MONTOJO: In 2022, the Dana Foundation awarded a grant to The Franklin Institute to revise its neuroethics curriculum to a new neuroscience and society curriculum that better captures the world that we live in today. Can you tell us about this project and why is it important? Who is it meant for, and what is its purpose?

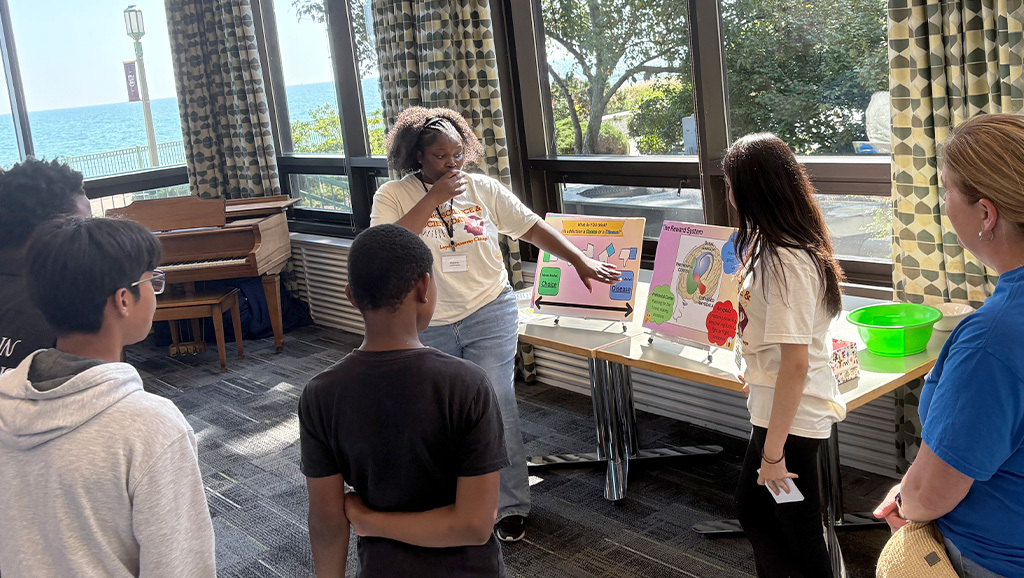

DAS: Absolutely. So, this was a project that we had started in a first iteration some years ago because when we opened your brain exhibit at The Franklin Institute back in 2014, we had developed a number of curriculum resources for teachers to really take the content of the exhibit and bring it into their classrooms. And so, in 2017, we had published this first version of the curriculum, but what we realized just three years later was that the science had changed; neuroscience was advancing in ways that weren’t represented in the curriculum. More importantly, the world had changed. Whether we’re thinking about all of the social justice movements that came to the forefront in 2020, when we think about the pandemic and how that really shaped our understanding of science and society, it was really clear that the curriculum as it stood, wasn’t really the right curriculum anymore. And so, we had taken it offline, recognizing that there was so much rich content there that needed some time and energy to become what it could be for the new world that we’re living in.

MONTOJO: How can teachers access this curriculum?

DAS: We’re really excited to make this curriculum free on The Franklin Institute’s website. One of the things that we’ve really done to flush out the usability of it is to restructure the curriculum in a format that I think teachers will really find familiar. So, thinking about engaging students first with a little hook that piques their interest. Then letting them explore with an activity that is really self-driven so that students are really discovering these key concepts for themselves. Then the teacher can dive deeper with all of the “Explain” materials. We call this the Four “E” Model, right? So, we’ve engaged, we’ve explored, we’re explaining, and we’ve really kind of brought out narratives around the highlights of neuroscience to make it easy for teachers to organize the material. And then finally, the “elaborate” is the fourth “E,” where students are now, again, engaging in really self-driven activities: a lot of dialogue, conversation, exploratory activities, looking at simulations to apply, again, what they’ve learned, and make those connections to the real world. It’s designed for high school level students, but we’ve already talked to teachers and middle school levels who are thinking about how they can maybe take some activities and level down. And we’ve talked to university professors who are looking at how they can level up into higher-level college neuroscience classes. So, we think that there’s a lot of room for flexibility.

MONTOJO: Another question. Do instructors need to have a science background to teach this content?

DAS: At the heart of this curriculum, it is still a neuroscience class. So, the way that we’ve structured the curriculum, the first lesson and the first unit, are pretty foundational neuroscience—covering a lot of core content like brain function, anatomy, how do neurons communicate, and so a science teacher would probably be best equipped to teach that. But once you get past that, it’s a little bit of a “Choose Your Own Adventure,” where the other units explore topics ranging from education to mental health to criminal justice. And so, there’s certainly many connections that you can make where, even if it’s not a science class, I think a teacher can grasp enough of the science to start appreciating how science informs these other areas of our lives and how they can bring that into many different aspects of education.

MONTOJO: I really want to take the curriculum myself. I learned neuroscience in a much more dry—[Laughs]. It was, like, in classes, more about memorization and understanding the basic facts, but being able to understand how it applies to different aspects of life was something that wasn’t really taught in that way at the time.

DAS: Your experience really speaks to the strength of this approach. One of the things that we learned from evaluating the curriculum with pilot schools was that participating in this course really had the biggest impact on girls, on students who had initially the lowest interest in neuroscience, and students who initially had the lowest interest in science in general. And so, I think it speaks exactly to what you’re picking up, that allowing the science to exist in this broader world really allows a lot more entry points for different students to get engaged and excited.

MONTOJO: Did anything surprise you as you updated and revised this curriculum?

DAS: I think one of the things that we learned was, especially when you think about topics like mental health, how much more aware students are of these issues that connect neuroscience to their lives. And when we’re asking students from 5th grade to 12th grade about what topics they’re curious about, the human body, mental health is number one.

MONTOJO: What kind of impact do you hope that this curriculum is going to have on students?

DAS: I really hope that inspires them to keep learning. You spend so much of your life outside of these places, and ultimately, it’s your own interest—your own motivation—that drives your learning for the rest of your life. And if we can give you the tools to think critically about the science, to feel confident that you can engage with the science, and then think about how you apply it to the decisions that you make in your everyday life. Well, I mean, who knows where that can take a child?

MONTOJO: Jayatri, what can members of the science ecosystems, what can they do to strengthen the relationship between science and society?

DAS: We talk to so many scientists in the field who are really interested in learning more and in doing more, but they don’t always have the capacity to be able to do it. And so, the more that we can raise the awareness and enhance the value of doing this kind of work, I think the more people will be excited about participating. But the other thing that I like to think about is: How can we, as members of that scientific community, also be better citizens of our communities? And I really encourage everybody to—you know, we’re always wearing our science hats—but we can have so many different aspects of our identities that represent in the community. I’m present in my community in many different ways. And so that type of activity builds relationships. And, ultimately, that is at the heart of public engagement—that science and society are not two different things, right? Science is part of society, and society is part of science, but when you boil that down, it really comes to relationships between people. And so, let’s just try to be better humans and makes space for that in our science.