Impact Story

Getting People Talking: Promoting Public Engagement with Neuroethics

Claire Weichselbaum, Ph.D.

Dana Foundation Barbara Gill Civic Science Fellow Claire Weichselbaum, Ph.D., has been working with the National Informal STEM Education Network (NISE Net) to develop new approaches for public engagement with the ethical and societal impacts of neuroscience. Based at Arizona State University in Tempe, her work focuses on two major themes: neurotechnology and modeling human attributes, or “what makes us human.”

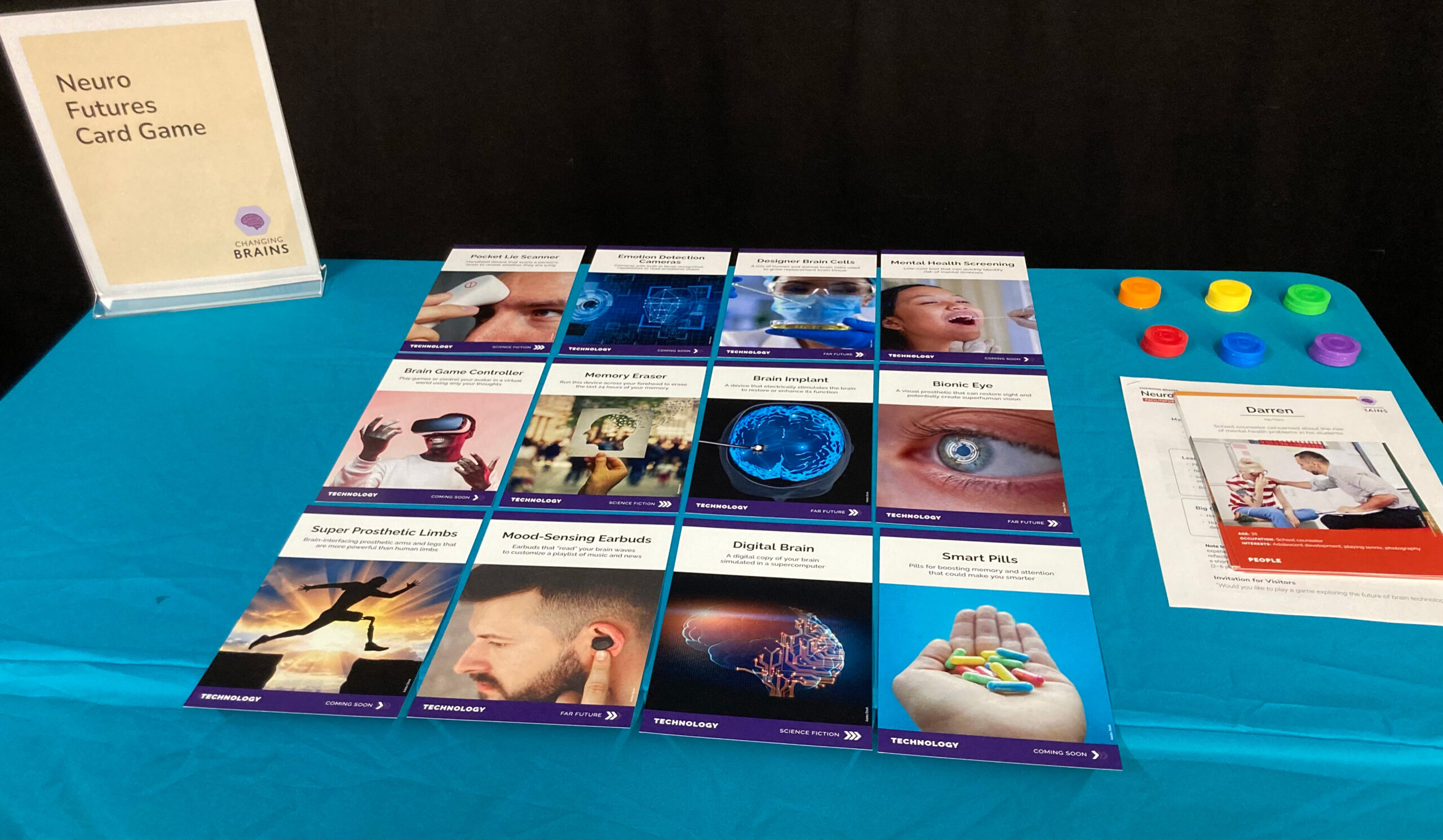

One tool she created, the card game Neuro Futures, invites participants to prioritize a variety of future and emerging neurotechnologies, first from their own perspective and then from a fictional one—stepping into the shoes of patients, caregivers, parents, students, lawyers, and members of the military, among other perspectives. Another, What Makes Us Human, invites people to consider which of our brain’s abilities are most uniquely human, and then design a fictional robot that incorporates some combination of these abilities.

Both activities are freely available to download, along with training videos and other resources, on the NISE Network website. A formative evaluation was conducted with 130 visitors at the Arizona Science Center, which found evidence that participants in these activities practice interpersonal skills such as communication, collaboration, and empathy as well as demonstrate personal attributes such as curiosity, creativity and imagination, and reflexivity. More than 95 percent of participants found the activities interesting, and many commented on how much they enjoyed the opportunity to explore their own and others’ values and perspectives on these important topics.

Q: Your 18-month fellowship was to develop innovative approaches to neuroscience public engagement, focusing on the ethical and societal implications of neuroscience research. Did you come up with this topic, or was it already decided when you applied?

Weichselbaum: As I understand it, the idea for this fellowship goes all the way back to 2018, when the Kavli Foundation gave the NISE Network a seed grant to convene a conference on public engagement with neuroscience and society. They brought together a bunch of stakeholders to think about the state of the field—where the needs and opportunities might be.

Then in 2021, Dana Foundation President Caroline Montojo, who had previously been at Kavli, approached Rae Ostman at the NISE Network and said, you know, this could be a really great opportunity to bring on a fellow and do some of this work that we had dreamed about years ago. They crafted this specific position–within the larger Civic Science Fellows program – around neuroscience public engagement and, more specifically, neuroethics engagement.

I had recently finished my Ph.D. in neuroscience and knew I wanted to move away from the bench, into the education and public engagement space. I’ve discovered that the only thing I love more than doing science myself is sharing it with others! So when I stumbled on the job description for this fellowship position, I was pinching myself. It sounded like my dream job! I thought, “Are they seriously gonna pay somebody to do this? This is amazing.”

This is such a new area. You had to start at the beginning, interviewing many different types of experts before you could start creating and experimenting. Did you think you could create as many tools as you have?

The 18 months has certainly flown by! All the things that I’ve created during this fellowship are really just the tip of the iceberg. These are pilot projects, models. Certainly these tools can be used as they are–both in museum settings, where we developed them, and in lots of other contexts as well. But we’re also hoping that these initial resources will inspire others to come up with more ways to engage the public in this kind of open-ended dialogue. We’re hoping they serve as a case study in what neuroethics engagement can look like, which we hope will will grow to be something much bigger.

We want to show that the scientific community has as much to learn from the public as the public has to learn from the scientists. We all benefit from having more of that mutual learning—the science gets better and more reflective of the needs of society, and the public is more receptive and invested in the process.

With a lot of neurotechnology innovations, for example, there’s often concern in the scientific community about how these things will be received. They will be received a lot better if you’re listening to the end users and involved in the larger public discourse around potential societal impacts.

When we played one of the ethics games, it was surprising how deep people got so fast. What kind of reactions do you get from people who use the materials you’ve helped develop?

It’s been overwhelmingly positive. We’ve had museum educators who pilot tested the games with us decide to continue using them, even before the final graphic design was done; they were just so excited by the rich conversations they were having with visitors. When I presented on this work at the AAAS annual meeting, it was wonderful that people were not only receptive to what we were saying, but really eager and asking, “How can I—from my position as a a scientist, or an educator, or whatever—help to promote more of this mutual learning and dialogue?” We heard that from a lot of stakeholders.

Pilot testing an early version of one of her activities at the Arizona Science Center. Photo courtesy of Claire Weichselbaum.

Neuroscience can be an intimidating topic for educators who aren’t neuroscientists. Even if people aren’t intimidated, they don’t necessarily have good tools and resources to go beyond “let’s make a brain hat and learn the parts of the brain,” which is all well and good, but sometimes you want to move the conversation beyond that. We’ve been hearing a lot of interest and appreciation for creating these tools that scientists and educators can use to to go a little deeper.

Sometimes we also get a little skepticism: How is this actually possible, within the current institutional structures of academia and the the lack of incentivizing scientists to engage with the public in this way? If it’s not getting them published or helping them get tenure, can they afford the time? But we have to start somewhere, and it’s very encouraging that there’s so much interest and curiosity about what this could look like.

How do you see this work continuing, post-fellowship?

We have plenty of ideas for how we would love to continue this work. For example, how might these kinds of public engagement tools be applied to a variety of different stakeholder groups? There are certainly many gaps to bridge besides just scientists and general publics, including policymakers, patients and patient advocacy groups, trainees, industry and tech, the list goes on.

Our small-scale formative evaluation gave us a very promising early signal that, yes, participants are getting something out of this. They are practicing the skills and personal attributes that we’re trying to promote through these activities, things like collaboration and reflexivity and empathy. But I would love to to do some more-rigorous research to see what exactly people are coming away with from these experiences, and how it prepares them to be more engaged with these topics in the future.

In 18 months, we were able to get some finished products that we can send out into the world and they can get some good use, but there’s a lot more we’d like to create and a lot more we’d like to do. There are all sorts of opportunities.

Have you been following the Foundation’s Neuroscience & Society Center plans?

Yes! That is definitely going to be an avenue for some of this dialogue to happen. These science and society centers will bring together scientists, ethicists, communicators, students and educators—all sorts of people.

We need these kinds of spaces where members of the public can engage directly with scientists on more of an equal footing, not just “I’m going to go hear a lecture at this university and sit and listen.” There’s a place for that too, but we also need opportunities for dialogue.

To have a leading organization like the Dana Foundation recognize that, see value in this kind of mutual learning, really lends this approach the legitimacy that it needs to become more of the standard – an expectation that this is something that we as scientists need to be thinking about. Neuroscience is so interwoven with society in so many ways; we’re going to need everyone’s contributions to realize the promise of brain research and technology.

What’s next for you?

I’ve just accepted a position as an Education and Engagement Specialist at the Allen Institute in Seattle, where I’ll be continuing to engage the scientific community, members of the public, and students from K-12 through college and graduate school in exploring cutting-edge neuroscience, as well as cell biology and immunology. I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity that this fellowship has given me to build my skills in this area, to meet so many wonderful people, and to launch my career in civic science – building these much-needed bridges between science and society.