News & Insights

Kafui Dzirasa: Innovating Neuroscience for Equity and Mental Health Impact

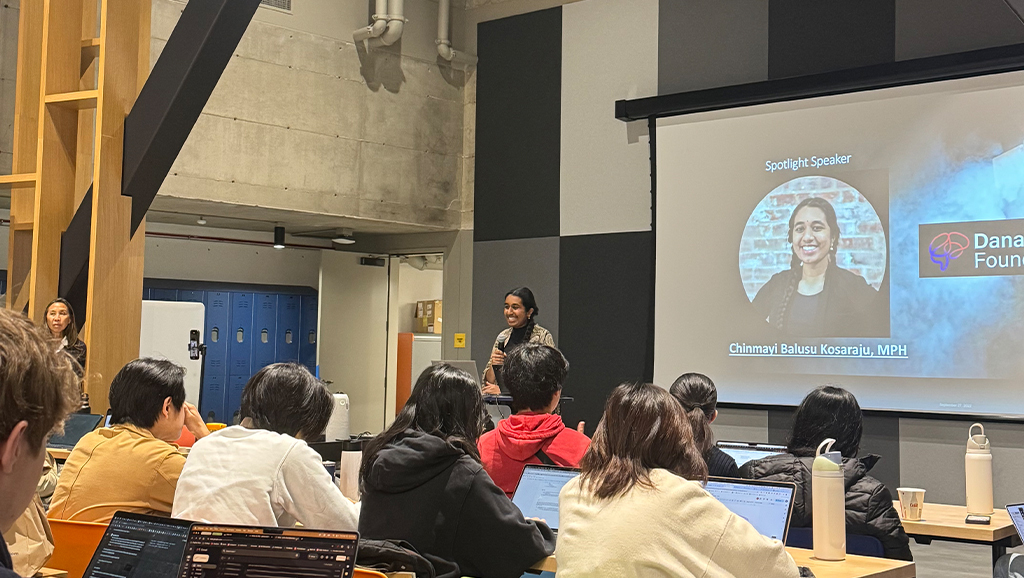

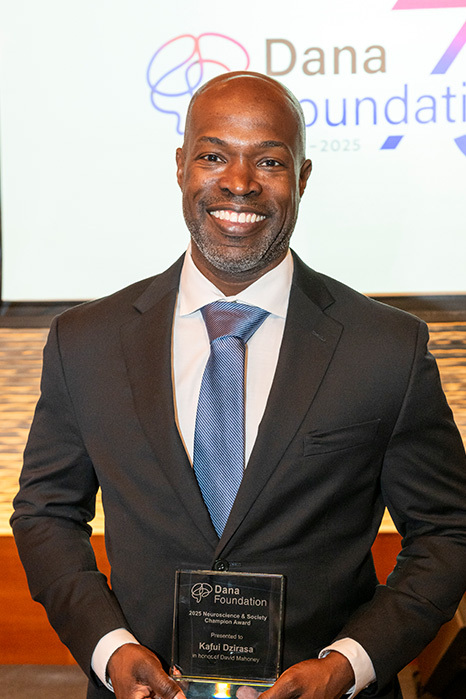

Recipient of the Dana Foundation Neuroscience & Society Champion Award, in honor of David Mahoney

Photo courtesy of Justin Cook for STAT.

Kafui Dzirasa, M.D., Ph.D., a pioneering neuroscientist and engineer who is advancing our understanding of brain activity to transform mental health treatment was honored by the Dana Foundation on June 12, as one of two inaugural recipients of its Neuroscience & Society Champion Awards. As the A. Eugene and Marie Washington Presidential Distinguished Professor at Duke University and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, Dzirasa combines neurobiology and engineering to create groundbreaking tools—such as “brain pacemaker” technology and a new model for analyzing emotion—to treat depression and anxiety. Here, he reflects on his career, mentorship, and the long road to creating meaningful change in people’s lives, their communities, and throughout the world.

Q: Your scientific journey started at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). How did your early experiences shape your scientific mission and commitment to diversity in research?

Dzirasa: When I began my undergraduate studies at UMBC, I joined a scholarship program dedicated to bringing diverse voices into science. It was spearheaded by philanthropist Robert Meyerhoff, who was motivated by the stark and troubling statistic: An African American male in Baltimore City was more likely to end up incarcerated than to earn a bachelor’s degree. Partnering with Freeman Hrabowski, they crafted an initiative focused on dramatically increasing Ph.D. attainment among historically underrepresented students. My cohort was intentionally diverse, representing America’s full range of talent.

This experience shaped my scientific vision profoundly. Since then, three core commitments have guided my journey: thinking deeply about Baltimore and the local communities impacted by science; recognizing how transformative science can truly improve health outcomes; and tirelessly working to ensure science is inclusive and driven by diverse perspectives. These foundational values motivate every step in my career.

You’ve played a central role in the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative (AANRI). What drove you to address the genomic research gap affecting communities of African descent?

My research has always been inspired by a desire to serve people, particularly families like my own. But during a conversation at the Lieber Institute in Baltimore, I realized an unsettling fact: The genomic databases underpinning much of the neuroscience research had literally excluded individuals of African ancestry. While publicly known to a degree, it still shocked me to discover that the scientific studies I relied on specifically left out large populations—like many in my own family.

This wasn’t merely concerning from a scientific perspective, it deeply troubled me personally. The genes I studied in the lab, the very foundation of my research aimed at curing mental illnesses, might not have relevance for my own loved ones.

That realization galvanized me to join this initiative, working closely alongside brilliant colleagues from various sectors, including local pastors, to build trust in communities traditionally excluded from neuroscience research. We’ve now successfully enabled family members and loved ones to partner with us by contributing tissue from their relations who have just passed—invaluable biological data we can use to pursue inclusive discovery.

With studies like these, it’s very easy for somebody who’s entrenched in disinformation or misinformation to pick it up and just say the top line is “Black brains are different.” And so, we were quite aware of that and really needed to highlight for people that this was not a study about intelligence. It’s a study about biology and how, by understanding the biology, you can improve medical outcomes—not just for those of African ancestry, but for everybody.

You speak passionately about the power of multidirectional, community-driven partnerships. Why is building trust and collaborative relationships essential to your science?

Scientists often communicate rigorously among themselves, but rarely in ways that build public trust. From my experience with the AANRI in Baltimore to my current work with the “Happy Dog Project,” I quickly learned the crucial importance of partners who have deep relationships, trusted voices, and cultural understanding of the community context. Honestly, even if you are entirely altruistic and have excellent intentions, meaningful change cannot happen without these relationships.

These partnerships highlight how good science isn’t just about rigorous methodology; it’s about genuine dialogue, trust-building, and mutual respect. I couldn’t do any of my current work without having learned this early—partnering equally and sincerely with community leaders, families, advocates, and other stakeholders outside academia.

Your work pioneered the concept of a “brain pacemaker” for mental illness. How did that groundbreaking idea originally emerge, and eventually evolve?

Early in my career, I became inspired by cardiology and saw the power of using electric patterns to detect illnesses through electrocardiograms (EKGs). What if we could apply a similar logic to the brain, listening closely to brain rhythms to identify patterns of mental illness and then intervening to correct them?

Driven by this idea, my lab embarked on an ambitious journey to build brain-stimulation technology, a sort of “brain pacemaker,” designed to treat conditions like depression or anxiety by adjusting abnormal electrical patterns.

We made exciting scientific progress, but I experienced a profound turning point after a conversation with my uncle, who asked: “How would this help people in the third world?” In that question I saw clearly a deeper challenge: The solution I’d thought revolutionary might not help the vast majority of people globally due to scalability and accessibility barriers. It was humbling.

That conversation significantly reshaped my research, motivating me to rethink projects from their inception to ensure solutions would benefit all people, not just those privileged enough to have sophisticated clinical access.

Mentorship is clearly integral to your professional and personal commitments. What drives this deep commitment to mentorship?

After completing my 15 years of clinical and scientific training, I wanted to give back to the folks who invested so much in me. What began as simple, monthly mentoring visits with the current Meyerrhoff Scholars turned into an extraordinary opportunity: I realized I wasn’t just donating my time—I was investing strategically in extraordinary talent. Soon I began recruiting UMBC students directly into my lab at Duke, creating a vibrant mentorship pipeline.

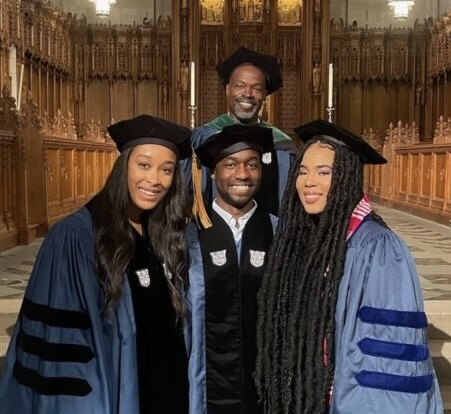

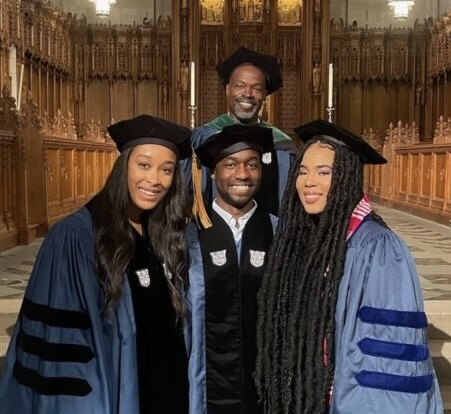

Seeing three Meyerhoff Scholars, whom I’d mentored closely, graduate simultaneously from my lab was an incredible validation. This mentoring has grown deeper and wider, not merely at Duke but throughout Baltimore institutions like Morgan State University. Recognizing the vital role these relationships play, I made sure mentoring was built into my formal contract. It’s not a side passion; it’s foundational to who I am as a scientist and human being.

Photo courtesy of Gwenaelle Thomas.

You’ve creatively leveraged your Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) funding to build a partnership with North Carolina Central University (NCCU). Why did establishing this shared program become such an important goal for you?

A while back, I had a mentee who’d completed his undergrad at NCCU, mere miles from my Duke lab. He ultimately earned an M.D.-Ph.D. through a partnership between Harvard and MIT. When I learned that, it truly felt like a missed opportunity. I couldn’t believe such remarkable talent was essentially in my backyard without my noticing it sooner. Not long after, another NCCU graduate won a MacArthur “genius” grant. That moment crystallized for me that I needed to rethink and strategize how I engaged with this tremendous resource.

HHMI funding offered an opportunity to tap into this remarkable talent pool practically next door. To put it in perspective, North Carolina Central has an endowment around eighty million dollars, while HHMI provides about eleven million dollars per individual investigator—so I realized the transformative potential of strategic resource-sharing. NCCU students consistently demonstrate inspiring drive and profound insight, often balancing intensive schoolwork with full-time jobs and other life responsibilities.

With the HHMI support, we built meaningful collaborations—joint appointments, shared projects, mentoring pipelines—that allowed us to bring NCCU students directly into innovative neuroscience. As I learned from my experiences building trust-driven, multidirectional relationships, effective collaboration means you always rely on partners deeply embedded in the community you seek to engage. Bringing robust science and deep community ties together not only benefits all involved institutions—it ultimately advances better science and stronger communities.

What insights or advice would you offer the next generation of scientists passionate about engaging with both neuroscience and society?

Remember first: Your credibility and skills as a scientist are what open the doors into these broader conversations. Early in your career, focus deeply on developing competence, mastery, and rigor—build that scientific toolkit.

At the same time, start practicing authentic relationship-building. Learn the art of collaboration and how to lead in diverse groups. Intentionally expose yourself to ideas beyond your immediate expertise. The truth is science and society aren’t separate; they’re intimately connected, each informing and improving the other.

Engage deeply, patiently, and consistently. Cultivate trust and clarity, invest in long-term relationships, and always strive toward practical solutions that clearly benefit everyone involved. You may not solve the biggest societal problems immediately, but if you’re patiently building scientific strength and nurturing relationships, when those pivotal moments come, you’ll be ready—toolkit in hand—to create meaningful, lasting change.

Recommended Reading

Karen Rommelfanger: A Neuroscience & Society Champion of Ethics and Inclusion

Dana Foundation Recognizes Two Neuroscience & Society Champions with Inaugural Awards