Impact Story

Meeting in the Middle

Equipping Middle School Teachers to Help Students Connect Science and Society

Middle school, typically grades six through eight, is often described as the “wild west” of education. The combination of rapid developmental changes, peer pressure, emotional volatility, and varied cognitive abilities means teachers are juggling more than lessons—they often must act as role models and referees, too. In many ways, one could not think of a better time to introduce the concepts of neuroscience and society—especially given the brain’s influence on this developmental stage. Yet, despite the growing number of neuroscience education and awareness programs geared towards elementary and high school students, specific content for middle schoolers has been historically lacking.

Alissa Mayers

“When kids are very young, neuroscience programs have been able to engage them with physically-based activities to help them learn about the brain. In high school, they are building an academic resume for college, and they can do more critical thinking type of work to learn about brain-based concepts,” said Alissa Mayers, director of public programs at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute for Mind, Brain, and Behavior. “Yet, in middle school … [t]here’s been a natural void of sorts because people haven’t thought about how to approach middle schoolers with this kind of information.”

For more than a decade, the Zuckerman Institute has organized a variety of research, community, and cultural programs to provide what Mayers calls “strategic pathways for access to science.” These include both formal and informal programs intended to nurture curiosity and build scientific skills.

“Our programs are designed to address a specific demographic, a specific need,” she said. “We are able to provide that by asking the community what they need and then trying to determine how we can fill those voids.”

Addressing a Gap in Middle School

To date, Zuckerman’s signature programs have included Saturday Science, which recruits local scientists to provide free and fun science activities for young students on a monthly basis, and BRAINYAC, a hands-on mentorship and training program for high schoolers. They also offer two programs for teachers: the Teacher Scholar program, a paid professional development opportunity for secondary school educators that teaches fundamentals about brain science and how to integrate it into their curricula, and the BrainSTEM in Action program, a one-day professional development workshop for high school teachers that focuses on a single topic, like the neuroscience of anxiety.

Diana Li, Ph.D.

When Diana Li, associate director of Education and Training Initiatives at Zuckerman queried the dozens of teachers who had participated in these different educator programs, she said one specific need kept resurfacing.

“These teachers told us that they observed students coming into ninth grade without certain skills—and that these were skills they wished those students could strengthen before starting high school,” Li explained.

“Especially after the Covid-19 pandemic and so much virtual schooling, teachers wanted more ways to foster dialogue with these students … so we started to think about the information ecosystem that surrounds middle school students and how we might train teachers at that level to be more confident about talking to their students about neuroscience concepts and to do so in a way that was engaging and interactive.”

Reframing Classic Concepts with Relevant Examples

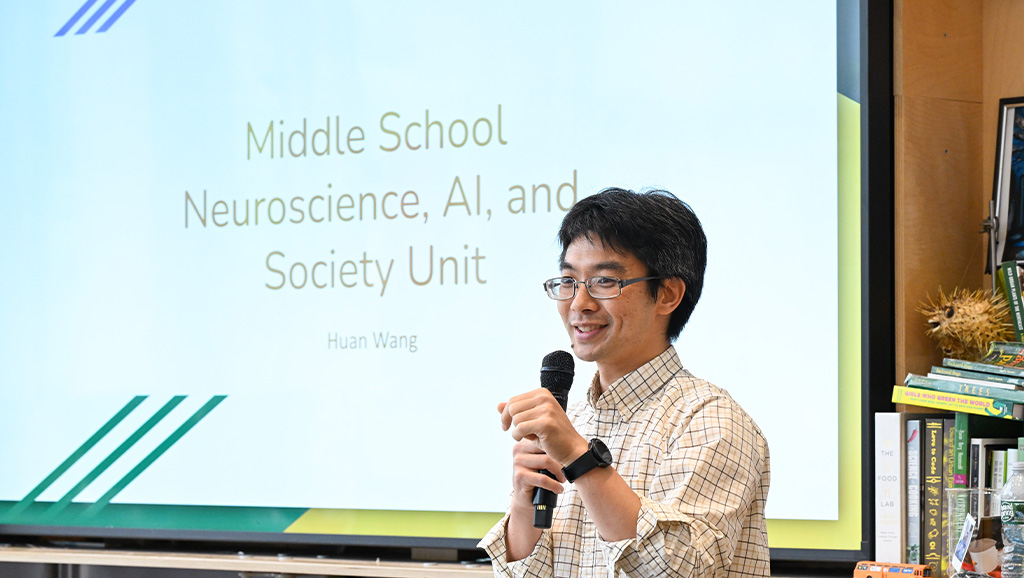

In 2024, the Zuckerman Institute enrolled its inaugural class of twelve middle school teachers in the program designed to do exactly that–the Teacher Institute for Neuroscience and Society. Supported by a Dana Foundation grant, this program is developed to help teachers at the forefront of the “wild west” of education by addressing adolescent-specific topics like neurodiversity in the classroom, brain-based learning and decision-making, and the role of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in schools. The first two cohorts of teachers each participated in a comprehensive workshop held over four days.

“The program allowed the teachers to engage with scientists, who were experts in these topics, and then design a lesson plan based on what they had learned,” said Mayers. “At the end, the teachers presented a capstone project focusing on one topic they felt was exciting or interesting to them. Many of the teachers developed public service announcements (PSAs) or short videos about those topics. And it gave us a preview of what they might ask their students to do in the future.”

Photo courtesy of TIFNAS.

Mayers, Li, and colleague Melinda Miller, senior director for Institute Programs and Outreach at Zuckerman, conducted both pre- and post-workshop surveys with the teacher-scholars to understand whether the content was helpful.

The surveys asked the participants how strongly they agreed with statements like:

- “I feel confident incorporating new and emerging topics relating to neuroscience and society into my teaching.”

- “I know where to find scientific and evidence-based resources or references for my own learning as a teacher.”

- “I have a strong knowledge base about how to approach conversations on multifaceted issues with students.”

Mayers said the surveys demonstrated a significant increase in teachers’ confidence engaging their students on brain-based topics.

“They became more comfortable in finding age-appropriate, scientific, and evidence-based resources,” she said. “And they felt they received formal training in neuroscience that helped them understand how neuroscience relates to society and how to share why this kind of science matters to their students … While many of the teachers felt like brain science was important at the start of the workshop, pretty much every participant felt it was overwhelmingly important that they were able to teach these topics to students to help them enhance their developmental skills after completing the workshop.”

Li added, beyond the post-workshop survey, she was pleased to see feedback from attendees that said they felt much less intimidated by neuroscience-based lessons.

“We heard from teachers that they now realized they don’t have to know or teach everything about these topics,” she said. “They can foster a dialogue and get their students thinking about it. And I think that’s equally as powerful as this traditional notion of coming away with specific content knowledge about a technical, scientific topic. They felt like they had the tools and the connections with other teachers to engage students in a beneficial way.”

Mayers added that this kind of program also has another extra benefit: The intersection of neuroscience and society can help teachers better understand the developmental nuances of adolescence and help them build more empathy for their students.

“So often, the way we teach students these days is with a very structured curriculum. With all the benchmarks and assessments, we can lose sight of all the things these kids are going through,” she said. “My hope is that we can empower conversations that will allow the teachers to think more creatively about how to engage students and interact with them to help them learn—not just in their classrooms but across the entire student community.”

An Evolving Program

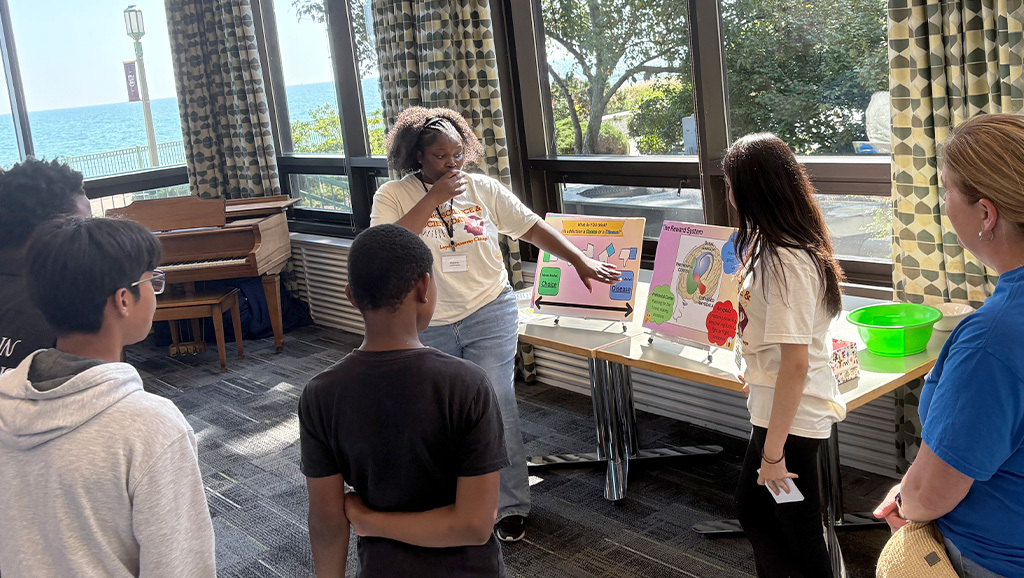

After hosting the two first workshops in 2024 the Zuckerman team invited participants to a Teacher Institute Summit to not only showcase the different lessons they executed in their classrooms, but to help shape how the Teacher Institute for Neuroscience and Society program would be conducted in the future. Miller said, once they got the participants back together, it quickly became clear that there was an accessibility issue—many teachers in their circles would have liked to participate but simply did not have the time to do so.

Middle school teachers participating in the Teacher Institute Summit. Photo courtesy of TIFNAS.

“Some teachers have the time to spend four days in a row at a workshop, but only at very specific times, and then only if they are lucky enough not to have any other life obligations,” said Miller. “Since we want to bring in as many teachers as possible, we realized that we’d have to change the format so more people could join us.”

Other feedback, Mayers said, included that teachers were excited more about specific topics, especially around social media use and AI. As a result, they required the ability to do deeper dives into topics they found most relevant.

“Moving forward, we will engage teachers in one topic over four consecutive weeks—one evening a week for a two-and-a-half-hour lesson,” she said. “We also heard that teachers want additional resources, so we are currently building out a website that will host lesson plans on specific topics like ‘Social Media and Me’ and the ‘AI Detective Challenge.’ These are all lessons that other teachers created, and we are pulling them altogether to help any teacher who may want to engage with this material.”

The Zuckerman Institute has recruited a new cohort of middle school Teacher Scholars for a workshop starting in October 2025—but will be soon opening up applications for the workshop scheduled for March 2026. They have increased the class size, too, and hope to host 24 teachers from the local NYC community in future workshops. Li said she is excited to reach more teachers and help them understand that “pretty much every subject” relates to neuroscience in some way.

“By exploring topics that look like neuroscience or science in general, I hope that teachers quickly see how relevant it is, how many different fields and disciplines are involved, and how it impacts everyday life,” she said. “This is not just a science teacher program. It’s for all teachers—and it can help them understand that some of the biggest challenges in our society are related to the brain. And by helping their students understand that, they are in a position to make a huge impact to inspire those students so they can join in helping solve those challenges for all of us.”

Recommended Reading

A Summer of Inquiry and Interdisciplinary Professional Development

From Learners to Leaders: Youth Led Conversation on the Brain and Society