News & Insights

Misinformation Epidemic Raises Stakes for Solutions

One of Elon Musk’s first moves as the owner of Twitter was to retweet fake news, setting off alarm bells among misinformation watchdogs. Coming in the wake of a Facebook whistleblower’s revelation that the social media giant weighted negative reactions five times greater than positive or neutral ones in determining each person’s unique newsfeed content—giving emotionally charged postings a distinct priority—the moves raise serious questions about how social media fuels divisiveness in the name of “engagement.”

Peddlers of disinformation have long mastered the art of grabbing attention through cues that provoke strong emotions, capitalizing on our evolutionary instinct to react to shock or outrage. What’s new is the viral potential that social media adds. The dual infodemics around Covid-19 and election integrity have shown how fast bad information can spread, and the lasting consequences it can have on societal issues such as public health and democratic principles.

The weaponization of information has raised important questions for neuroscience as well as society. Up for debate is whether social media platforms can be expected to self-police newsfeeds, or if they must be forced to through government regulation, as is being considered in the US and Europe. Each option carries risks of censorship and authoritarianism.

Or should it be up to the individual to discern falsity from fact? What would that take, amidst fractured attention spans and a barrage of confusing and sometimes deliberately misleading messages?

While society debates the first questions, neuroscientists are grappling with the latter, testing several potential strategies that might help equip average people with the cognitive tools to identify and resist fake news.

Tapping Into Anger and Outrage

That was the pitch in a recent post on LinkedIn by a self-described “mad content scientist” who promised to coach followers on how to “provoke anger and frustration” in their copywriting to make their posts go viral.

Few people who use social media know how their newsfeeds are curated—that clicking the “angry” emoji on a Facebook post immediately triggers more posts of a similar nature, for example. But content managers of all stripes do, and they market it openly.

Educating people about how algorithms can target them is critical, Renee DiResta, a research manager studying modern disinformation at the Stanford Internet Observatory, said in a webinar hosted by Harvard Law last June. Part of the problem is transparency around algorithm decisions, as the Facebook whistleblower demonstrated. Users don’t know exactly what details about themselves or their behavior that these automated systems are using to decide what it will show them next. “We don’t have that visibility into how these [algorithms] are working,” she said. “What steers people’s attention is foundational.”

A Business Model Built for Misinformation

Humans are wired to respond to highly charged stimuli. Our attention system evolved to focus on strong emotional stimuli and surprise. We get sucked into anything that provokes an inflammatory response—the proverbial shock and awe. Fake news capitalizes on that. Marketers do too, including the social media companies themselves, whose business models rely on capturing our attention and provoking a reaction.

To Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive scientist at the University of Bristol, UK, who studies misinformation and how to combat it, that makes the idea of social media platforms self-policing their content for accuracy “like trying to get the fossil fuel industry to deal with climate change when their livelihood depends on them.”

“Social media is similar in the sense that they’re making their money out of a business model where our attention is the product that they’re selling to advertisers. The commercial incentive to capture our attention can be very much in conflict with giving us accurate information, because human attention is attracted to negativity,” he says. “There’s an incentive built into the business model to favor misinformation.”

This is one way social media algorithms “exploit the cognitive limitations and vulnerabilities of their users and fuel polarization,” Lewandowsky and Anastasia Kozyreva argue in an essay on the topic.

Pre-Bunk, Debunk, Nudge, Repeat

Increasing evidence suggests that misinformation that captures our attention in this way can drive lasting changes in thinking, even after a correction has been made and accepted. This phenomenon, called the “continuing influence effect,” has been replicated widely in laboratory experiments and is evident in historical examples where even widely debunked myths continue to be believed by large swaths of the public. A classic example is the persistence of the belief that eliminating weapons of mass destruction was the reason behind the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, despite the evidence never surfacing.

Debunking false information through post-exposure fact-checking and correction is one means that has been used on some social media channels, including Twitter pre-Musk. Studies show it can be beneficial—sometimes. The continuing influence effect seems to confound even the best debunking. Practicality is also a challenge: DiResta likened fact-checking to a perpetual game of whack-a-mole.

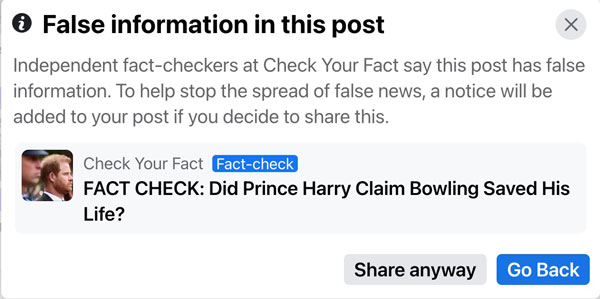

Debunking: On Facebook, posts can be labeled false, prompting people to think twice before sharing them.

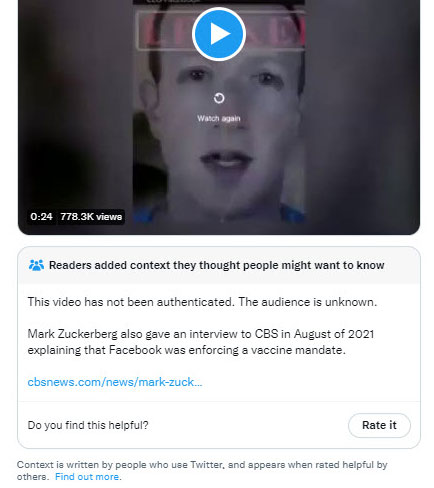

Accuracy nudges—the juxtaposition of context-relevant information alongside a post that has been flagged as misleading—are another strategy that has shown some benefit in alerting people to misinformation, under certain circumstances. The idea is to cause a pause long enough to allow a moment of deliberation, and sometimes that’s enough. Yet the benefits of accuracy nudges have not been reliably replicated in experimental settings, leaving open questions about when and how this tool might be best implemented.

Nudging: Twitter has had an option for readers to append a note to tweets videos they find misleading.

“Pre-bunking,” which is based on the concept of psychological inoculation, has emerged as a promising strategy. Unlike fact checks or debunking, pre-bunking seeks to pre-empt false information by alerting scrollers to the fundamental attributes of misinformation so they are better equipped to identify it. Jon Roozenbeek, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Cambridge, U.K., tested pre-bunking in a study funded by Google and published in Science Advances in August.

A ‘Vaccine’ Against Fake News’?

The premise for psychological inoculation came out of efforts by the US Department of Defense in the 1960s to help US prisoners of war resist “brainwashing” by the Vietcong. The idea was simple, analogous to a vaccine: Expose people to false information in a safe context so that when they are faced with that information later on, they have some cognitive power to resist the psychological hijacking.

The problem with applying that Vietnam-era iteration of pre-bunking is that “it’s very difficult to inoculate people against every individual sort of misleading argument they might be exposed to in the future,” Roozenbeek says. The list of lies a wartime opponent would tell a POW is limited. Even if one could predict every social media claim, the effort to pre-bunk each one would be overly cumbersome, just as fact-checking and debunking is.

Instead, Roozenbeek aimed to inoculate people against the underlying strategies that are used to misinform and manipulate, such as emotional arousal and logical fallacies like false dichotomies. He created short educational videos, which were presented on YouTube and viewed more than a million times, and found a significant though modest improvement in the capacity to identify false news among those who viewed them.

Based on the findings, Google is now rolling out one of the largest real-world tests so far of pre-bunking in Eastern Europe, an attempt to counter disinformation about Ukrainian refugees following Russia’s invasion of the country. (see more prebunking videos)

Is pre-bunking enough to fight back the onslaught of false information coming at people on social platforms? Not likely, Roozenbeek says. His study found roughly a five percent improvement in discernibility, and he’s openly skeptical of whether the Googles and YouTubes of the world can be entrusted to solve the misinfodemic.

Cognitive Armor

Pre-bunking tries to provide a bit of cognitive armor against misinformation by equipping people with tools to help spur critical thinking and separate fact from fiction. Education around media literacy and scientific literacy seeks to do the same, imparting fundamental principles such as source integrity and red-flag language. A number of approaches are being studied.

John Cook, a cognitive scientist at Monash University in Australia, created an online game called Cranky Uncle that teaches critical thinking through cartoon characters. An independent research group based at Max Planck Institute in Germany calls its version of digital literacy training the “science of boosting,” offering practical tips and evidence-based strategies such as lateral reading to assess a source’s accuracy. The News Literacy Project provides educational materials to teachers and the public, including a 60-minute video tool to help people be more critical consumers of news and information. Its website says its materials were used by 16,000 teachers to reach 2.4 million students last year.

Formalizing media or science literacy classes into school curriculums has been slow, with only Illinois requiring it. Without a mandate, teachers are largely on their own to find evidence-based resources and incorporate them into class teachings.

Doctors Against Disinformation

Driven in part by the avalanche of Covid misinformation, medical professionals are increasingly jumping into the fray to set the record straight on medical misinformation. Physician-educators like molecular biologist Raven Baxter (aka Dr. Raven the Science Maven) and public health translator Katelyn Jetelina (aka Your Local Epidemiologist) have garnered huge social media followings and regularly take on medical falsehoods, sometimes in unorthodox ways, like Baxter’s viral vaccine rap.

In June 2022, the American Medical Association adopted a 9-point anti-disinformation strategy that includes educating health professionals and the public on how to recognize disinformation as well as how it spreads and encouraging state and local medical societies to engage in dispelling disinformation in their jurisdictions.

In his 2021 advisory, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called health misinformation “a serious threat to public health” that “can cause confusion, sow mistrust, harm people’s health, and undermine public health efforts.” He called for a multi-pronged effort to combat it,

Taking a cue from Vivek, New York City’s health department set up a dedicated Misinformation Response Unit that worked in partnership with trusted messengers from within communities—particularly marginalized and non-English-speaking communities—to detect and debunk misinformation since the early days of the pandemic. Writing in NEJM Catalyst, the program’s directors said the Covid-19 pandemic “has made clear that responding to misinformation is a core function of public health” and called for more research to determine best practices.

Shikha Jain, a Chicago-based medical oncologist and activist, had been using her social media platforms to disseminate solid medical information before the Covid-19 infodemic blew through the internet. The barrage of misinformation around the pandemic led Jain and two colleagues to found Impact, a nonprofit that amplifies healthcare workers’ voices to communicate evidence-based medicine and science in a simple manner.

“We’re using everything from social media posts and infographics to writing op-eds and letters to the editors, TV and news interviews, to writing statements and policy suggestions.”

Now she and her colleagues are taking the lessons learned to the next generation of medical professionals with a new course at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine. It’s part of a handful of pilot projects funded by the American Association of Medical Colleges at five US medical schools to kickstart disinformation curricula for medical students and allied health professionals in training.

Andrea Anderson, a family physician and senior medical consultant to the AAMC who is working with the grant recipients to develop best practices, said the need has never been greater. “Traditionally, medical trainees have not been specifically trained how to navigate patients that may be hesitant or may possess inaccurate information, pseudo-scientific myths, or disinformation that might be harmful to that patient.”

“Physicians and other health care providers are trusted messengers within our society,” Anderson said in an interview. “This is a role that we take an oath to inhabit. We need to work to provide our patients with the most accurate information to help them make healthcare decisions for themselves and their families.”

Silver Buckshot

No single strategy to combat disinformation is likely to be enough, says Lewandowsky. “We don’t have a silver bullet. We have silver buckshot. We can throw out a lot of little things that we can show make a difference under controlled circumstances.”

Part of the conundrum, Lewandowsky says, is that these various strategies “have not been compared under identical circumstances on the same playing field.” Hopefully, he says, that will change within the next 12 months because of a new initiative called the Mercury Project, a multi-site consortium that will conduct the types of direct comparisons necessary to evaluate the differential benefits of each of these strategies.

For his part, Lewandowsky is skeptical that any combination of these “buckshot” measures can fully dismantle the disinformation machinery of those who seek to intentionally mislead the public—particularly in light of the changes now underway at Musk’s Twitter.

“It requires systemic change. We shouldn’t pretend that coaching individuals through little videos or pie charts will do the trick,” he says.

Governance, Lewandowsky argues, is the crucial need, whether it’s self-governance by the platforms or top-down regulation by legislators.

“The problem of misinformation is inextricably linked to the algorithms used by the platforms. The fact that these algorithms are essentially hidden from the public means there is no accountability for what they’re doing.

“To me, that is the serious big issue, that we have a very small number of people in Silicon Valley determining the information diet of much of the world without any accountability. We have permitted that to occur, and now we have an uphill battle to introduce accountability into the system.”

Recommended Reading

The Lights and Shadows of Science and Technology

Neurotechnology for People: Dana and the Brain-Computer Interface Frontier