According to the US Chamber of Commerce Foundation, the world is in the midst of a global science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workforce shortage, which is becoming more daunting as the number of jobs requiring STEM expertise continues to grow. While there are many reasons students do not ultimately pursue STEM degrees, several studies have highlighted limited exposure to foundational STEM concepts, perceptions of overly challenging classes, lack of relatable role models and mentors, and courses that seem disconnected from day-to-day life.

Bill Rochlin, Ph.D.

With such a dire need for more STEM graduates, many academics are looking for ways to increase not only numbers but diversity in scientific fields. Bill Rochlin, Ph.D., a developmental neurobiologist at Loyola University Chicago, said events in 2020, including the death of George Floyd, sparked reflection across the university about how to better cultivate feelings of safety and inclusion on campus. He said he immediately started to think about how to increase representation in neuroscience.

“The university was already doing things to encourage students who were already at the university to get into research and go the STEM route,” he said. “But I noticed, in my classes, not only were women and people of color underrepresented—the students who were there weren’t particularly interested in going into research after graduation.”

This, Rochlin said, made him wonder if college might be too late a start to encourage students to pursue a STEM career.

“I wanted to create something that could reach students who are taking science classes for the first time,” he said. “It didn’t take me long to realize the way we teach STEM—the way we introduce STEM—can be very sterile and disconnected from society. And that might be part of the reason why we aren’t attracting more students.”

STEM Introduction by Ethics-based Teaching

If you ask young students to describe a scientist, they will often depict a white male in a lab coat, pouring an unidentifiable liquid into a test tube. They likely aren’t thinking about STEM researchers as people outside of a lab who are working to address greater societal issues.

“Historically, the goal has been to be as efficient as possible to teach the nuts and bolts required to have a scientific career. We don’t talk as much about the ethical issues that are inherent to scientific work,” he explained. “Because of that, we may be inadvertently selecting people who are ‘book smart’ but aren’t as interested in science and technology’s impact on society. We may be missing out on people who are really interested in considering the ethical ramifications of new discoveries and technologies.”

Elizabeth Wakefield, Ph.D.

To address this, Rochlin, in partnership with Loyola colleagues Elizabeth Wakefield, Ph.D., Joseph Vukov, Ph.D., and Demetri Morgan, Ph.D. (now at the University of Michigan), developed a new pedagogical approach called Ethics-Based Teaching Helps Optimize STEM (ETHOS), a program that introduces neuroscience through a combination of foundational concepts and open discussions about the ethics and societal implications surrounding scientific advances. Rochlin said the idea came to him after teaching one of his capstone courses for molecular/cellular neuroscience majors.

“We spend a couple of days in that class talking about ethical issues—for example, the brain and criminology: Are you guilty of a crime if you have brain damage or a tumor that changes your behavior in a criminal direction?” he said. “I noticed that the discussions were often led not by the students who were excelling in the rest of the class. It was the kids who didn’t do as well on exams.”

Rochlin said this revelation helped him recognize that students don’t need a deep background in STEM in order to debate neuroscience’s influence on society. But, more importantly, ethical discussions were a great way to help students more meaningfully engage with the scientific material.

Joseph Vukov, Ph.D.

The ETHOS team developed a series of ten after-school workshops for high school juniors to explore ethical issues surrounding criminology, virtual reality, drug addiction, and more. Vukov said the group worked hard to put together topics that had enough “substance” to support a debate.

“We wanted to give the students enough of the science so they could understand what was going on—and then enough of the ethics so they could start to see what some of the issues are from a societal standpoint—so they could have a genuine back and forth discussion about it,” Vukov said. “We found the students were really interested in talking about these issues. They had a lot to say.”

Liliana Whipple, a local student at Senn High School who participated in the workshops, said she found the workshop on drug addiction particularly compelling.

“The workshop explored addiction from more of a medical standpoint than a moral or choice standpoint,” she said. “We read an article by Carl L. Hart [a psychologist at Columbia University who argues for the legalization of drugs], and it changed my perspective on so many things. It made me backtrack and really think about a lot of the stuff I’d been told [about addiction] growing up.”

But, Rochlin said, if the goal is to recruit the next generation of researchers and do so with greater representation, the ETHOS program also needed to provide students with an opportunity to do science. So, after students completed the series of workshops, they had the opportunity to work in Loyola University Chicago’s labs over the summer.

“They work half-time in the lab four days a week and then, on the fifth day, we provide professional development training like guidance on applying to colleges,” he said.

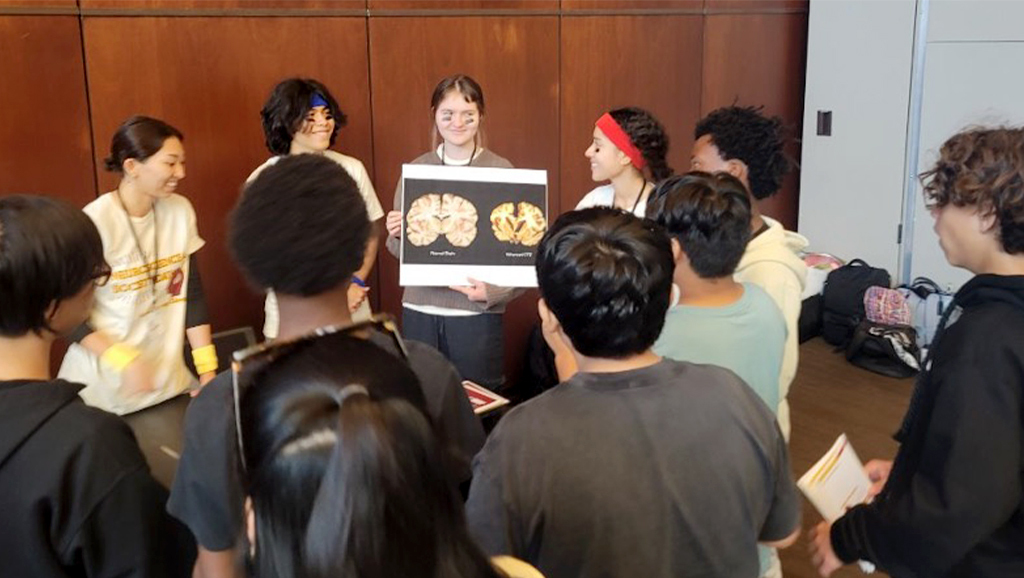

That lab work also helps students develop the skills required for the third component of ETHOS: a near-peer mentoring event. After students work in the lab, they can develop activities based on their research work to share with middle school students in their own neighborhoods. It’s another way to increase relatable scientific role models, Rochlin said.

“The high school students lead these activities,” Rochlin said. “The idea is to empower them to become instructors or guides. And then the middle school students can see people who look like them leading these efforts.”

Measuring Efficacy

The ETHOS team was awarded a two-year $1 million grant from the Dana Foundation to roll out the unique program. The funding was part of the greater Dana Center Initiative for Neuroscience & Society, a multi-million-dollar initiative to help “co-create the future of neuroscience,” through new approaches to connect scholars and society to promote neuroscientific research that supports a better world.

“ETHOS is clearly a very immersive and unique way to introduce neuroscience to high school students,” said Kathleen Roina, director of the Dana Foundation’s Education program. “After observing a workshop, I feel like it’s creating young citizens that are in tune with the ethical, societal, and legal implications of this field of study. It’s helped to make them more literate in neuroscience and understand how neuroscience knowledge is relevant to their everyday lives.”

The research group has been tracking the program’s efficacy through pre- and post-program surveys and interviews. One of the things they measured, Wakefield said, was STEM identity, or how confident each student is that they are a “STEM person,” with plans/intentions to pursue a career in a STEM field.

“The idea is to ask students to evaluate how they see themselves, as well as how they think others see them—how much overlap is there between that student and a STEM practitioner?” she explained. “We had a very small [sample size], only 14 students completed both the pre- and post-survey, but we saw a trend moving toward them feeling more confident about being a STEM person. And that’s really promising.”

Wakefield added that interviews demonstrated that students are thinking about STEM in a more “nuanced” way.

“In the pre-interviews, some students said they wanted to be a doctor but couldn’t really articulate why,” she said. “After the program, however, we got much more detailed answers. Students talked about where they could help people, or the different ways the STEM careers they were interested in could make a difference. It showed their progression through these discussions helped them better understand the connections between the jobs they were considering and the potential societal issues involved.”

Whipple, for her part, said that as someone who has been told she is “artistic,” the program helped her realize that there were opportunities for creativity in the sciences, even if she doesn’t want to pursue a career as a physician.

“Being able to think about using my creative abilities to approach scientific problem solving was new to me, but really interesting,” she said. “And, after doing the research work, I realized being in the lab could be a good career option for me that I hadn’t really considered before.”

Scaling Up the Program

The current data on ETHOS is preliminary, said Rochlin, but very promising. So much so that he is already thinking about how to scale up ETHOS: not only to more schools, but to include more STEM disciplines like engineering. He said he thinks it’s a better way to do STEM education—and engage students where they are at.

“There’s been a really enthusiastic response to ETHOS,” he said. “We’d like to go nationwide, if not internationally. Phase Two is getting the ETHOS idea incorporated into the classroom. The workshops have been great, but that approach usually attracts students who are already interested in a STEM career.”

He added that, the research work for students is limited to high schools in the near vicinity of universities with science programs—but the workshops could work as a standalone option for schools all over the world.

“We’d really like to get to a point that—even in basic science classes—everyone can learn science and research are not just exclusively reductionist, but also important to society,” he said. “I think we’d find a lot more people are interested in pursuing science if they understood all the ethical impacts to their lives and communities.”