The business of wearable brain devices, promising benefits that range from improved mood to the betterment of age-related decline, is booming.

The digital brain health market, which includes wearable brain devices, is likely to grow to $6 billion, likely more, by 2020, according to SharpBrains, an independent market research firm that looks at brain science applications. Technology companies already are marketing brain recording and stimulating devices directly to consumers. Are these companies adequately—and ethically—educating consumers about both their benefits and risks?

An Unmet Need

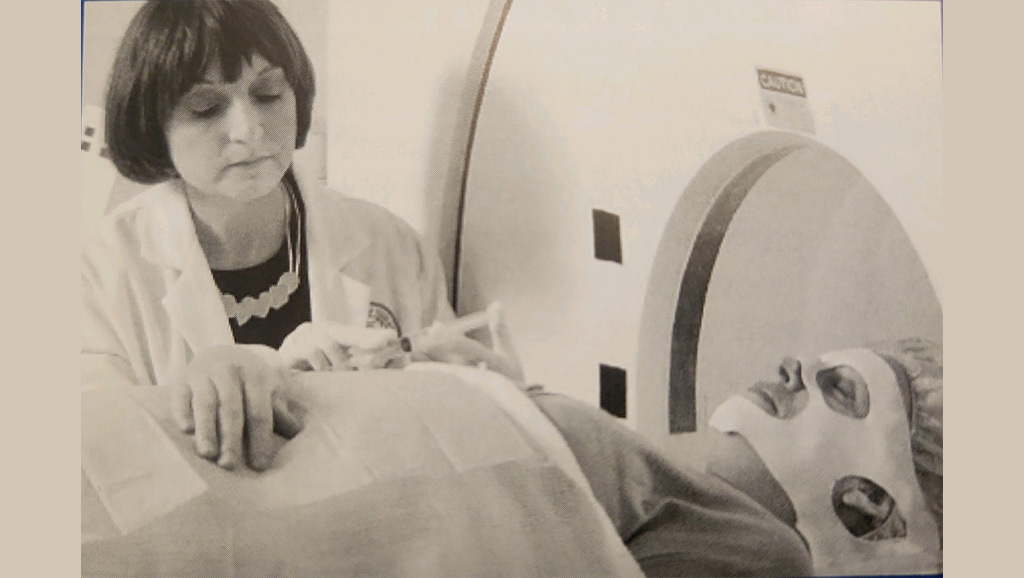

You can find many wearable brain devices directly marketed to consumers–and easily available for purchase on the Internet. Several of them contain sensors that can measure your brain activity, much like an electroencephalogram (EEG), while others provide direct electrical stimulation to your scalp. The companies say their products can improve attention and memory, reduce stress, or even help gamers improve their scores on their favorite video games. Some even claim that their devices “may” help manage neuropsychiatric conditions like depression or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or help slow the progress of dementia.

Alvaro Fernandez, who runs SharpBrains, says that there is an unmet need for such innovative technologies. “Conditions like depression and Alzheimer’s disease cost society billions and billions of dollars,” he says. “Current drug treatments don’t work for everyone and they often have a lot of side effects. There’s a lot of opportunity here to help people who may have these medical issues. But, in addition to that, the reason why this market is growing so quickly is that people want to find ways to enhance their brain health at any age. They don’t want to experience that cognitive decline if they don’t have to. So, there is another great opportunity for companies to develop tools that can help with that.”

Like the nutritional supplement industry, though, there are few regulations or oversight when it comes to wearable brain devices. Most devices don’t have, and are not required to have, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to go to market. So consumers must trust the very companies who develop and market these products to explain both the potential benefits and risks of their use.

Laura Cabrera, an assistant professor of neuroethics at Michigan State University’s Center for Ethics and Humanities in the Life Sciences, says we should be skeptical. While many studies suggest that techniques like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), have the power to curb depressive symptoms, improve sleep, and help with focus and memory, Cabrera says, it’s important to remember that such results come from strictly controlled lab experiments, not ad hoc at-home tests.

“We know that these technologies have the power to affect our brain. We just don’t know the level of detail of how they are affecting our brains. How do they work? What are they doing? What kind of damage might they bring about in the short or long term?” she says. “In the lab, you have a protocol that controls how many sessions, the duration, and the intensity of these methods. But when you leave it to the consumers to make those decisions, it’s really difficult to know, or even anticipate, what the harms could be.”

Examining the Ethical Issues

Given how quickly neurotechnology innovation is occurring, it is vital that society takes a close look at the validity of claims made by companies who are selling wearable brain devices directly to consumers, says Judy Illes, professor of neurology and Canada Research Chair in Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia.

To see whether or not they were ethically and accurately educating consumers about the potential benefits and harms of these products, Illes and a team of neuroethicists examined 41 wearable brain devices currently for sale, not to evaluate their effectiveness but rather to better understand how they were being marketed and sold. Their results were published in the May 22, 2019, issue of Neuron.

Illes says that she expected to find “heavy emphasis” on benefits in the marketing materials, and she did. But she was surprised to find little attention paid to potential risks.

“We found very little discourse around risks, and the kinds of risks they did address were quite incomplete,” she says. “These devices can result in an itchy scalp or burned skin from overuse, but there was very limited information on that. They also didn’t talk about the risks of using these devices in lieu of more traditional treatments. Since some of these devices are being marketed to people with disorders, some of the most vulnerable people in our society, our team felt it was very important that they offer specific warning messages about not using these devices to supplant conventional forms of medication or instead of pursuing care from healthcare providers.”

Furthermore, if the devices are shown to work, actually affecting brain processes, Illes says companies need to also explain to consumers on how the devices might affect brains still developing in childhood and young adulthood and brains with illnesses that cause degeneration.

“The risk information really needs to be front and center,” she says. “Companies need to take ownership of the ethics of their innovations, not relying on external regulatory systems to intervene.”

Cabrera strongly agrees with Illes. “We don’t have great certainty about what such devices can do—and we don’t have a regulatory system that truly protects consumers from those potential harms,” she says. “So, for me, companies need to be responsible, transparent, and safe. It’s up to them to make sure that consumers understand all the potential risks of use.”

Moving Forward

We will see the market for wearable brain devices continue to expand, industry expert Fernandez says, especially as large technology players like Google and Microsoft become more involved with the development of digital brain health tools. He argues that people at these companies are thinking very carefully about the ethics involved in the use of such devices.

“They are getting more interested in working with neuroethicists and thinking through the risks as they work to channel innovation in ways that can really help people,” he says. “The challenge will be to make sure they are assessing these devices properly so they make sure the people who really need them can access these tools, and so they are maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks.”

Illes says she thinks that more companies are willing to take the kind of ethical ownership she recommends. Many of the neurotechnology developers are working with neuroethicists to make sure they are including ethical thinking into their development cycle. And, ultimately, she argues, it will help them succeed in a market that is only poised to grow.

“Any entrepreneur, any innovator or company in neurotechnology that isn’t including an ethics lens to what they’re doing in some form, whether light or strong, will fall behind,” she says. “When it comes to potential changes to the brain, I don’t think that our society will accept this kind of innovation without an ethics component to it.”