Fact Sheet

Understanding Mood

Who this is for:

Mood is a word people use to mean a lot of things. You may wake up in a “bad mood” when you haven’t slept well. You find yourself in a “good mood” after time with friends or loved ones. We often talk about “mood swings” or “mood altering” experiences, and some people even call one another “moody.” When we are frustrated or fed up with a particular situation, we are “in no mood” to deal with it. We even listen to “mood music!” So, what is mood, exactly? And what does it have to do with the brain?

What is mood, exactly?

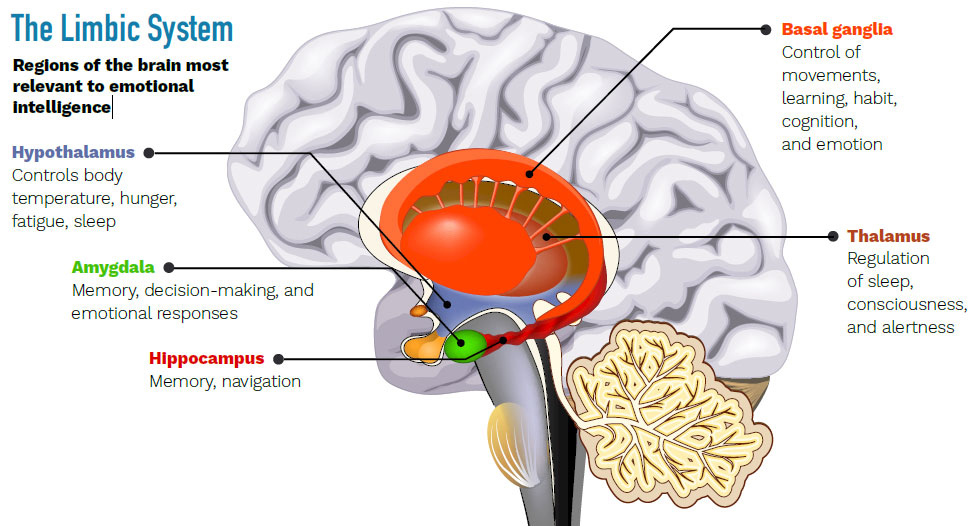

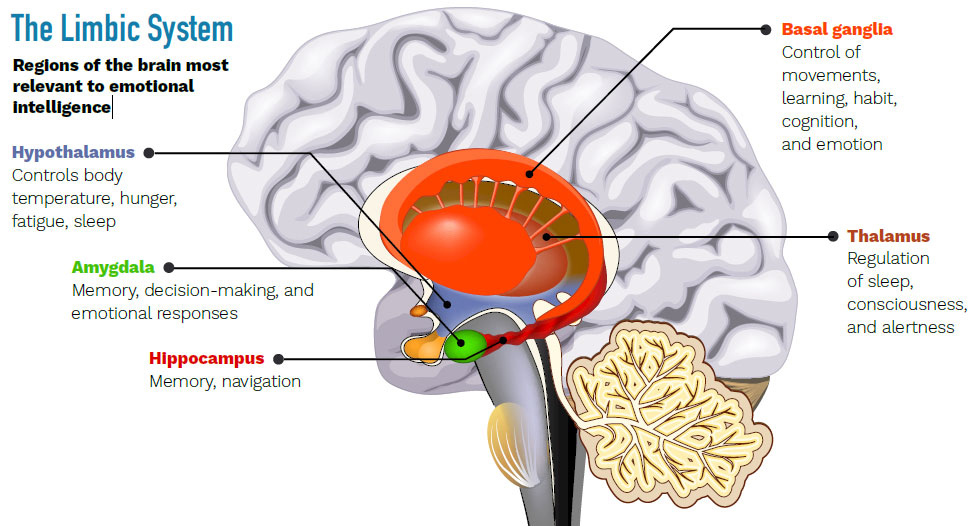

The brain is responsible for thoughts, feelings, and actions. Those feelings we experience are emotions. Brain regions including the amygdala, the insula, and the periaqueductal gray – just to name a few – are part of the brain’s limbic or emotion system, and are responsible for summoning these feelings. This system helps us to seek out the things we both want and need, protect ourselves from harm, and socially connect with others. Emotions tend to be intense, depending on the situation you find yourself in and, for the most part, last only a short time, soon to be replaced by the next feeling you need to help you navigate the world around you.

Moods are a little different. To start, they last longer. The American Psychological Association (APA) defines mood as “a disposition to respond emotionally in a particular way that may last for hours, days, or even weeks, perhaps at a low level and without the person knowing what prompted the state.”

Moods tend to echo particular emotions, like happiness or sadness, but they are usually less intense and more persistent—a state of mind that lasts for an extended period of time. While emotions tend to be linked to a particular person or event, moods may not be connected to any obvious cause. And while moods may not be as strong as some feelings, they do have power. Many studies have shown that your mood can influence perception, motivation, decision-making, social interactions, and even more basic cognitive processes like memory and attention.

How is mood related to depression? What about other psychiatric or neurological disorders?

It’s quite common for your mood to shift over time, much as your emotions do, but they tend to do so in a slower fashion. But if your mood, particularly if it’s a negative mood, starts to get in the way of your work and family life, then it can become a problem doctors call a mood disorder. As you can imagine, problem moods can range widely, from low energy to too much energy, from mildly harmful to daily life to incapacitating. Some conditions that are listed under the umbrella of “mood-based disorders,” per the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), include depression and bipolar disorder.

Sometimes this persistent change in your general emotional disposition can be due to what’s going on in your life at the time. But scientists are also learning that genetics, medications, medical issues, and other factors can alter neurotransmission in areas of the brain linked to mood, like the hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala. These areas are also part of the limbic system, but are specifically involved in mood regulation, part of the brain’s greater emotional processing duties.

Depression, for example, is a mental health disorder where a person experiences a persistent dampening in mood, or persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness. While it’s very normal to experience a depressed mood sometimes, when it lasts for two weeks or more, leading to loss of interest in the things you normally enjoy and isolation from the people you care about, it can cause a lot of other problems. Those issues can include harmful changes in sleep, energy levels, appetite, and concentration. Severe depression may also lead to feelings of suicidality.

While common wisdom holds that a chemical imbalance in the brain leads to depression, particularly too little of an important neurotransmitter called serotonin, it’s actually a lot more complicated than the lack of a single neurochemical. While many studies have shown serotonin’s importance to mood and emotional regulation, the brain relies on many neurotransmitters to communicate vital messages between neurons. Already, scientists know that several other neurotransmitters, including but not limited to dopamine and norepinephrine, also help in regulating mood.

Bipolar disorder shares some aspects of traditional depression—in the past, it was even called manic-depression. But this mental health disorder is characterized by dramatic shifts in mood, where an individual unexpectedly swings between a period of depression to an extremely elevated mood state. During the e upswings, known as manic episodes, people can have intense energy, racing thoughts, distractibility, and increased risk-taking behaviors.

Doctors recommend if you are experiencing a depressed or extremely heightened mood for more than two weeks – and it is interfering with your ability to live your life – it’s time to seek help from a medical provider.

Why are teens so moody?

Any parent can tell you that teenagers display a sometimes-alarming amount of emotional volatility. They’re up, they’re down, and you never quite know how they will react to a particular event or person. The reason? Puberty.

The same hormones that are helping an adolescent grow into their adult body are also facilitating explosive growth in the brain. Since the brain has specific receptors for hormones like testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone in different parts of the limbic system, heightened levels of these chemicals may lead to teens having an exaggerated emotional reaction to different situations—and a variety of reactions to the same type of situations at different times.

The good news is that it passes as teens gain more experience to help them regulate their moods and emotional states. But adolescence is also the time where many people first experience symptoms of a neuropsychiatric disorder. If you or a teen you know are struggling with mood-related symptoms to the point where it is interfering with school or family relationships, it’s time to reach out to a medical professional.

How can you improve your mood?

You can do quite a lot to boost a negative mood. Thanks to neuroplasticity, the ability of neural networks in the brain to change through growth and reorganization, actions you take can help your brain work more effectively. Studies have shown that regular cardiovascular exercise, ample sleep (7-8 hours each night), nutritious foods (that include nutrients like Omega-3 fatty acids, selenium, and B vitamins), and even meditation can help lower stress, regulate hormone and neurotransmitter levels, and improve your mood. Spending some time out in the outdoors, getting out into the sunshine, and spending time with others also has been shown to help. And for those who struggle with mood disorders, there are medicines and therapy methods that can teach you helpful self-talk (like cognitive-behavioral therapy) to improve your mood over the long term.