Fact Sheet

Understanding Seizures

Who this is for:

A seizure, simply defined, is a sudden change to the electrical activity in the brain. These changes can affect both brain function and behavior, from muddled thoughts to violent convulsions.

What happens in the brain during a seizure?

Our brains oversee every thought, feeling, and action using a process called neurotransmission (sometimes called synaptic transmission). The billions of neurons in the brain talk to one another using electrochemical signals. When a cell has been stimulated, it generates an electric potential–a charge, so to speak–to help it send a chemical message to its neighbors. There are both excitatory (positive) and inhibitory (negative) electrochemical signals. During a seizure, the normal waves of excitatory and inhibitory activity fall out of balance, which can lead to uncontrolled surges of electrical activity in certain regions of the brain.

Are there different types of seizures?

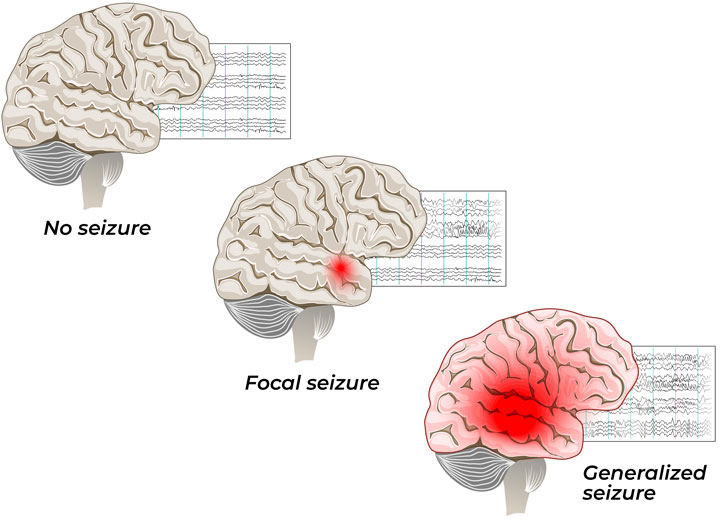

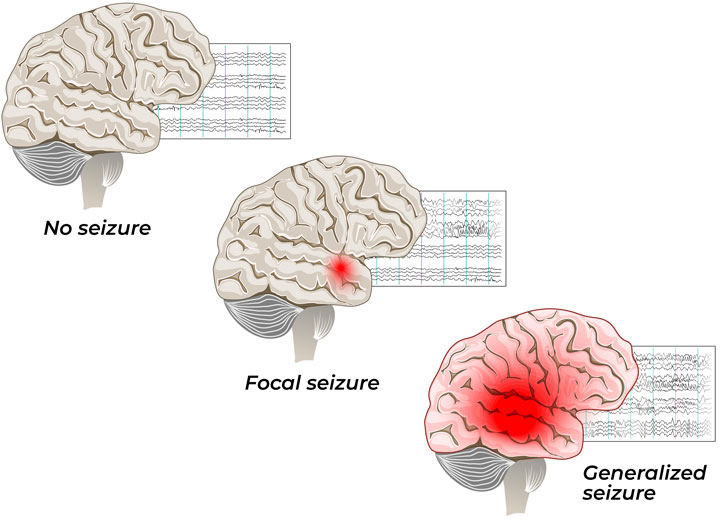

Yes. Seizures can be caused by many different things, including epilepsy, congenital brain malformations, severe hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), high fever, stroke, and other brain diseases. Given the range of different causes, it makes sense that there are many different types of seizures. Seizures are generally classified into two groups. Generalized seizures are those that affect both sides of the brain. Focal seizures, sometimes called partial seizures, affect one region of the brain. Focal seizures are usually the result of a stroke or brain injury, and leave scars in the brain that interrupt normal electrical activity. Over time, damage from focal seizures can lead to generalized seizures.

You may also hear people talking about:

Simple or complex focal seizures. The symptoms can start off as quite mild—in fact, you may not even realize a seizure is occurring. People who experience simple seizures may notice twitching or changes to their sensory perceptions, such as strong tastes or smells. Complex focal seizures, on the other hand, may lead to confusion, minor shaking, or muscle stiffening.

Absence seizures. Once referred to as petit mal seizures, these types of seizures usually occur in children between the ages of four and six. They can be easy to miss, because it looks to an observer that a child is simply staring off into space briefly or blinking rapidly. Most children grow out of them before puberty.

Myoclonic seizures. These seizures involve sudden, jerking movements in the body.

Tonic and atonic seizures. Sometimes called “drop attacks,” tonic seizures, or seizures where the body’s muscles dramatically stiffen, usually occur in people who have had multiple brain injuries. Atonic seizures are just the opposite, where the body suddenly loses muscle tone and control—but this type, too, commonly results in falls.

Tonic-clonic seizures. This type is often seen in popular movies or television shows, and the type that people think about when they hear the word “seizure.” They used to be called grand mal seizures, and they tend to involve violent muscle contractions, convulsions, and a loss of consciousness. These seizures are usually the result of epilepsy.

What is epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a form of seizure disorder. People with epilepsy may be genetically predisposed to seizures or they may develop the problem after a serious brain injury. While, for some, seizures may just be due to a temporary issue—perhaps a high fever or extreme low blood sugar event—epilepsy is chronic medical condition, with reoccurring seizures that will have to be managed over a person’s lifetime.

How are seizures treated?

Prevention: Because seizures can result in falls, injuries, and, in rare, severe cases, brain damage, most treatments involve trying to prevent the seizures from occurring in the first place. A doctor may recommend certain medications or dietary changes to help. Unfortunately, many people who have epilepsy cannot get relief from the medications that we have now. They may need surgery to install deep brain stimulation or other electrical devices that monitor and head off the storm, or surgery to remove damaged parts of the brain.

Can you trigger a seizure?

Unfortunately, yes. People living with epilepsy often see an uptick in the number of their seizures because of stress, sleep deprivation, or drug or alcohol use. Missing a dose or two of their prescribed medication can also bring on a seizure. While less common, seizures can also be triggered by bright, flashing lights or loud noises, which is why you sometimes see warnings on movies or games that use strong, light-based special effects.

What have epileptic patients taught us about the brain?

Quite a bit! In the 1950s, neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield was able to map different regions of the brain and associate them with different functions by stimulating different areas in patients who were undergoing brain surgery for epilepsy. A few decades later, people living with epilepsy who underwent “split-brain” surgery—which severs the corpus callosum, the neural tracts that connect the two hemispheres of the brain—helped neuroscientist Roger Sperry to understand functional differences between the two halves of the brain. In the years since, neuroscientists have done many more studies on people with epilepsy during surgeries to understand how the brain works. For example, today, the Allen Institute for Brain Science uses samples of living brain tissue donated by these patients to better understand the cellular and molecular properties of the brain.

What should you know if you see someone having a seizure?

This is important – as, thanks to all those movies and TV shows, many people immediately do the wrong thing. If you suspect someone is having a seizure, help ease the affected person to the floor and gently turn them on to their side. Make sure to clear the area of anything hard or sharp to help keep them from injuring themselves on it. While it is helpful to remove eyeglasses or loosen neckties, you should never put anything in a person’s mouth. Most seizures only last a minute or two, and you can just wait it out until the person regains consciousness and can easily communicate and answer questions. But if the seizure lasts more than five minutes, it’s time to call 911.