News & Insights

Building Trust, Breaking Down Barriers to Co-Creating the Future of Neuroscience

Guests attending the opening of the artwork created by Harlem-based artist Ivan Forde at Columbia University's Zuckerman Institute (2019). Photo credit: Sirin Samman.

What makes me me? What areas of neuroscience research will help the most people? How do you make bionic eyes? How close are we to knowing any of this?

When you open a conversation with people about the brain, a wellspring of wonder—and sometimes worry—pours out. Because neuroscience research and technological progress affects all of us, it makes sense that all people should be involved in shaping how our societies employ neuroscientific findings and what we might try to learn next.

Americans have a lot of enthusiasm for brain health research, but scientists as a whole have not done a good job of engaging the public about what is going on, where they can get involved, and how they can become more integrated into the creation of science, said Ishan Dasgupta, J.D., program officer for the Dana Foundation, during a session at this year’s annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The session, “Co-Creating the Future of Neuroscience: Pathways for Public Engagement,” was part of the theme of this year’s meeting: “Science for Humanity.”

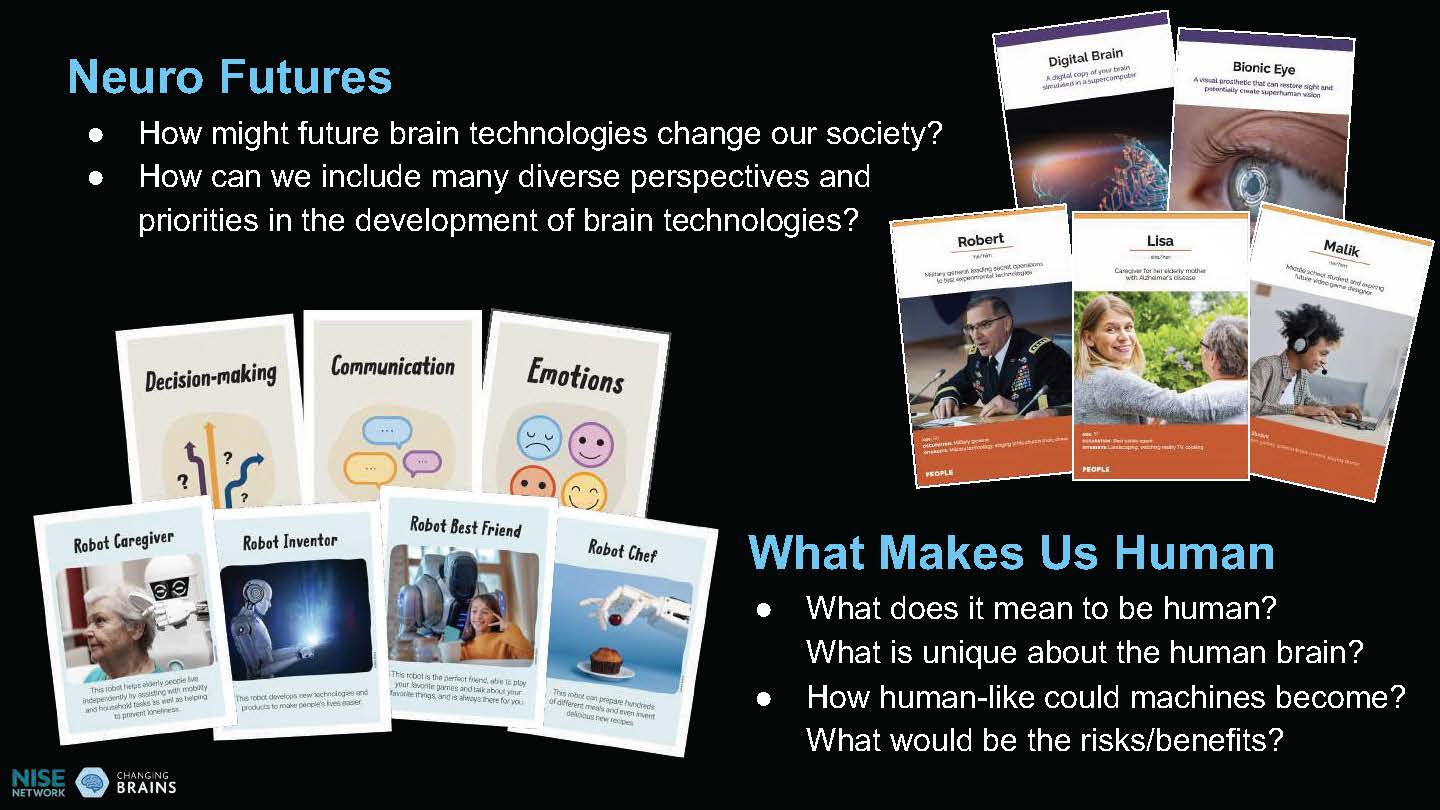

From left: Paula Croxson, Ishan Dasgupta, Claire Weichselbaum, Lomax Boyd Dasgupta shared data from a survey conducted by Research!America and the Dana Foundation that showed that most people in the United States have experience with brain health issues and want to have a voice in how the science is applied in our society and which streams of research should be prioritized. During the session, panel members shared the methods and results of several pilot projects that aim to make the goal of co-creating the future of neuroscience a reality. In Baltimore, Maryland, last year, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics took to the streets, going into the community to ask residents one question: If you could design a science experiment, what would you want to research? Then they played the responses to neuroscientists and recorded their reactions. (Listen to a sample of the dialogue) The project is ongoing, but already the researchers have found that non-scientists can ask inspiring and sophisticated questions, said panelist Lomax Boyd, Ph.D., of the Berman Institute. The scientists were energized listening to the range of questions and wanted to hear more. “Neuroscientists are interested in engaging the public, but there are a number of barriers to that kind of engagement,” Boyd said. “And the number one reason why folks didn’t engage is, ‘I don’t know anybody to introduce me to those people.’ There need to be systems and programs and processes for connecting.” In the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, scientists and science communicators at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute have joined with local arts groups to co-create experiences and activities targeted to their audiences. “We had a really flourishing educational set of programs, but we wanted to try to reach audiences of adults who may not be seeking science content directly,” said panelist Paula Croxson, Ph.D., formerly of Columbia and now a program director at the Dana Foundation. They began with museums and arts-based institutions that were embedded in the community, which had shown an interest in working with the university. “We came in and said, ‘Do you want to try something?’” Croxson said, pitching a one-off project, not a major commitment for the potential partner. It took time, up to two years, to build trust, create a partnership, and find ways to collaborate before getting the project off the ground. “We were very clear about what we could offer,” such as university staff time, access to scientists, and communications help, Croxson said. “And then we listened. We asked what was important to our partner. We asked them what they cared about, what their audiences cared about, what they thought that they would like to create. “Each of our partners is highly regarded in their community and expert in their own right. We didn’t consider that we knew everything because we were scientists, and we made sure that we thought about drawing on the assets that each of our partners brought with them.” This required giving up a lot of control, she said, often creating something the researchers hadn’t even imagined, and doing it in new ways. Under the banner “Breakout Science,” partners ranging from dance companies to a group offering museum-based experiences for people with dementia and their caregivers created experiences they knew their community would enjoy that also shared some science, “serving science on the side,” as Croxson put it. Organizers used the arts groups’ email lists and social connections to draw attendees; each group set the goals and survey measures they would use to decide if the event was a success. (See a video of the event Brain at the Barre, with the Dance Theatre of Harlem, and also more about Arts & Minds) “In each case, our partners came back to us with their feedback and described their joy during the event, and then reached out asking if we could do more,” Croxson said. “In every single case, we had the opportunity to start something new with each of our partners, and in the case of Arts & Minds, they actually started holding their programming on our property, in our spaces, just because it brought their participants so much joy to be in the science space.” A partner told the Columbia team that no one had ever talked with them about science, that “nobody talks to people with dementia about the brain.” Another avenue for informal engagement with science is fostering small-group conversations that can help people explore how they feel about a given topic—and imagine how others might feel about it—in a safe environment. At Arizona State University in Tempe, Dana Foundation Barbara Gill Civic Science Fellow and panelist Claire Weichselbaum, Ph.D., has been creating and testing approaches and tools aimed at two topics that came up often in her pre-research as ripe for public engagement: neurotechnology and modeling attributes unique to human beings. Courtesy of Claire Weichselbaum One tool, NeuroFutures, invites participants to prioritize a variety of future and emerging neurotechnologies, first from their own perspective and then from a fictional one. The characters are based on perspectives that different groups of people might bring to these technologies: patients, caregivers, parents, students, lawyers, members of the military, and more. Another, What Makes Us Human?, invites people to consider as a group what abilities are most uniquely human, and then design a fictional robot that incorporates some combination of these abilities. (Find freely available copies of these and more at NISE Network) “Despite the simplicity of these brief activities, people got into some pretty deep reflection and dialogue quite quickly,” Weichselbaum said. “We all bring our unique perspectives to this work, and these activities really surface that and allow people to reflect on what perspectives they might be able to contribute.” So far, she has collected observational and interview data from 47 groups of people; 96 percent of participants said they found the games interesting, and a majority said they would love to play again. Weichselbaum also found that, though the games were designed with older youth and adults in mind, kids as young as seven or eight could engage meaningfully with them when they played with older family members. “A number of parents commented that it was fascinating to see how their kids thought about these issues. I think we probably sparked some interesting dinner table conversation in some of these families,” Weichselbaum said. She invited everyone in the audience and who goes to the NISE Network website to download a game and try it for themselves, and then to share their thoughts with her. She hopes that these tools will be applied in a variety of contexts: promoting dialogue among different stakeholder groups, engaging students and trainees in debate about these issues, or any way people can think of. “It’s easier than you might think,” she said. “People are willing—and even eager—to share their perspectives, and we as scientists should be ready to listen.” How much of the science should people know before weighing in? Weichselbaum said, “You can very quickly get to the heart of the ethical and societal issues with surprisingly little explanation of how exactly the technology works, or the intricacies of the research. Not that those explanations can’t be part of public engagement, too, but they’re not a prerequisite for having these conversations. In fact, sometimes that can get in the way of truly listening to what members of the public bring to the conversation.” And everyone is an expert on their own values, Boyd said. It’s easy to see how some emerging areas of neuroscience and technology intersect with people’s belief systems. “Everybody deserves to be listened to in a way that’s meaningful,” said Croxson. “I think we’ve been doing a lot of public engagement, in neuroscience in particular, kind of listening to people, maybe serving people a little bit. Almost everybody that we engage with could do with a bit more of us closing the loop, talking about and sharing how meaningful those interactions are for the scientific community as well.”

Ask—and Listen

Let Community Experts Lead

Conversation Starters

How Much Science?

Recommended Reading

From Broadcast to Belonging: Dana's Public Engagement Evolution

Reciprocity in Neuroscience: Dana Foundation Panel at the UN Science Summit

Trust and Engagement in Neuroscience: Listening Must Shape the Future