News & Insights

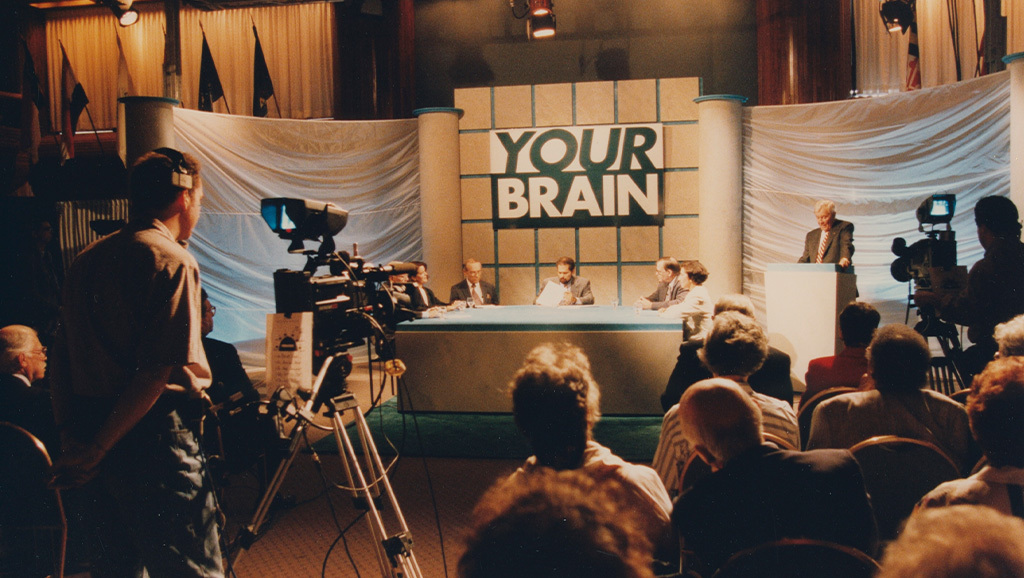

Reciprocity in Neuroscience: Dana Foundation Panel at the UN Science Summit

At the 80th United Nations General Assembly (UNGA80) in New York City, the Dana Foundation joined the global dialogue on health and development by hosting a panel during the Brain Days, organized by the European Brain Council in the framework of the Science Summit. The panel, titled, “Community-Partnered Neuroscience Research: Strengthening Trust and Engagement,” brought together scholars and practitioners to share their perspectives on how neuroscience can become more inclusive, relevant, and connected to the communities it aims to serve.

Joanne Berger-Sweeney

Opening the discussion, Joanne Berger-Sweeney, Ph.D., a board director of the Dana Foundation and president emeritus of Trinity College, reflected on the importance of understanding the role of society when using neuroscience to benefit the public. Her remarks underscored an ongoing shift in emphasis from how science can serve communities to how communities themselves can guide and shape the uses of science. In that spirit, she outlined the panel as an exploration of reciprocity, how neuroscience not only informs society but can also be enriched and made more impactful through societal insight, partnership, and trust.

The panel featured three speakers and was moderated by Arleen Salles, Ph.D., a philosopher and bioethicist who directs Neuroética Buenos Aires and serves on the executive board of the Institute of Neuroethics (IoNx). Salles opened the panel by framing the conversation around a question that surfaced repeatedly in the group’s preparatory exchanges: What do we mean when we talk about trust?

“We tend to agree that this work is about people,” Salles said. “But do people think it’s about them?” Trust, she noted, is more than a feeling; it is a relationship that entails vulnerability and context, shaped by moral, historical, and cultural factors as much as by scientific integrity.

That framing set the stage for a discussion that explored trust not as something “broken” that must be restored, but as a shared capacity to be cultivated.

Recent research supports this view: A 2024 study published in Nature Human Behaviour found that in most countries, public trust in scientists remains relatively high. A nationwide survey by Research!America in partnership with the Dana Foundation similarly showed that Americans place high importance on brain health and broadly support increased investment in brain research. Yet, as an analysis in Issues in Science and Technology points out, though there may not be a significant “anti-science” movement, perceptions of science are far from uniform, and many expect science to become more participatory, transparent, and relevant to their concerns.

The panel discussion built on this premise, focusing on what it takes to make neuroscience more responsive to public needs and perspectives. Humility, the panelists agreed, is a precondition for trust. It requires scientists to acknowledge the limits of their expertise and make space for the knowledge and values of others.

Drawing from her work in South Los Angeles, Ashley Feinsinger, Ph.D., of the UCLA-Charles R. Drew University Dana Center observed that trust grows through the “will and skill to engage in dialogue” rather than through one-way communication. This approach, rooted in human-centered design, begins by asking what communities are already doing to address an issue, and what they value in possible solutions, before asking what neuroscience can contribute.

This framing naturally moved the discussion toward how systems and structures can support this kind of bidirectional engagement. Paola Zaratin, Ph.D., director of scientific research for the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Society, discussed how patient and public engagement must move beyond inclusion as a goal and become part of research and policy design from the start. She described how measuring the “return on engagement” helps assess the real impact of patient and stakeholder input in shaping governance and accountability.

The conversation also extended into the civic dimensions of neuroscience, where Narayan Sankaran, Ph.D., assistant professor of neuroscience at the University of San Francisco and a former Civic Science Fellow at UC Berkeley’s Kavli Center for Ethics, Science, and the Public, reflected on how dialogue between scientists and publics can deepen ethical awareness. His work on brain-computer interfaces and neural decoding technologies illustrates how listening to communities can “complicate ethical thinking” by grounding scientific innovation in lived experience.

From left: Panelists Ashley Feinsinger, Paola Zaratin, and Narayan Sankaran.

These ideas are connected to broader conversations in civic science, as discussed in a Civic Science Fellows article about the panel that features relevant perspectives, including from Sankaran and Caroline Montojo, Ph.D., president of the Dana Foundation. The piece frames community-partnered neuroscience as part of a wider movement toward co-creating knowledge that is both ethically grounded and socially responsive, with Montojo describing this approach as one that makes science “deeper and richer than it would have been if done in a silo.”

Throughout the discussion at UNGA, humility and reciprocity emerged as recurring themes. Engagement, the speakers agreed, should not be about convincing communities to trust science, but about creating conditions in which science earns trust through relevance and transparency. “Engagement is not a one-off event,” as one panelist observed, “it is a sustained commitment to ask first, listen well, and return.”

The conversation also pointed to challenges beyond the hour allotted, such as how to design funding mechanisms that reward long-term partnerships, how to teach participatory methods within scientific training, and how to integrate local knowledge into policy at a global scale. These questions resonated with audience members, many of whom raised issues of neuroscience literacy and education.

In conversations following the event, participants, including professionals from across neuroscience and related fields with an interest in community engagement, remarked on the panel’s practicality, noting that it offered actionable insights and tested models for addressing these challenges.

The UNGA80 panel illustrated that neuroscience’s next frontier may not be only technological but relational: a practice of co-creating knowledge with the communities whose lives it touches. As community-partnered research continues to grow, the Dana Foundation’s commitment to advancing a neuroscience that listens, as much as it discovers, remains at the heart of that vision.