Impact Story

The Dana Foundation: Architects of Neuroethics

Sometimes, the real breakthroughs in science come not just from what we learn, but from the conversations that shape what that knowledge means—and what we do with it. This idea lies at the heart of neuroethics, a young and dynamic field born from the deliberate intersection of neuroscience and ethics. Rather than letting groundbreaking scientific findings about the brain unfold in a vacuum, neuroethics has emerged as a crucial space for reflection and dialogue on the ethical, legal, and societal implications of these discoveries.

Take privacy, for example. With brain-scanning technology improving every year, the idea that marketers can read our real reactions to ads—or that police could scan suspects’ thoughts—doesn’t sound like science fiction anymore. We have to ask: What does this mean for our freedoms and our society as a whole?

The Dana Foundation quickly saw that cracking the mysteries of the brain had to go hand-in-hand with considering the range of ways this knowledge could be used or misused.

William Safire

William Safire, then-chairman of the Foundation, summed it up at a landmark conference in 2002: Neuroethics is “the examination of what is right and wrong, good and bad about the treatment of, perfection of, or unwelcome invasion of and worrisome manipulation of the human brain.”

“The Dana Foundation has played an absolutely critical role in shaping the field of neuroethics,” said Anna Wexler, a member of the International Neuroethics Society and assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. The Foundation helped launch and shape the field of neuroethics, providing sustained support for innovative, interdisciplinary projects at the intersection of neuroscience and society, and championing its growth, accessibility, and public understanding.

Fostering these conversations can be tough. For non-scientists, neuroscience concepts can be intimidating. For neuroscientists, moving from one-way lectures to true dialogue—“learning from people who know things about society and politics and cultures that you don’t understand,” as the late neuroscientist Sir Colin Blakemore put it—takes commitment. The Foundation made that commitment early on.

Today, as brain science races ahead, these conversations, championed by the Dana Foundation, are more important than ever.

Starting the Conversation

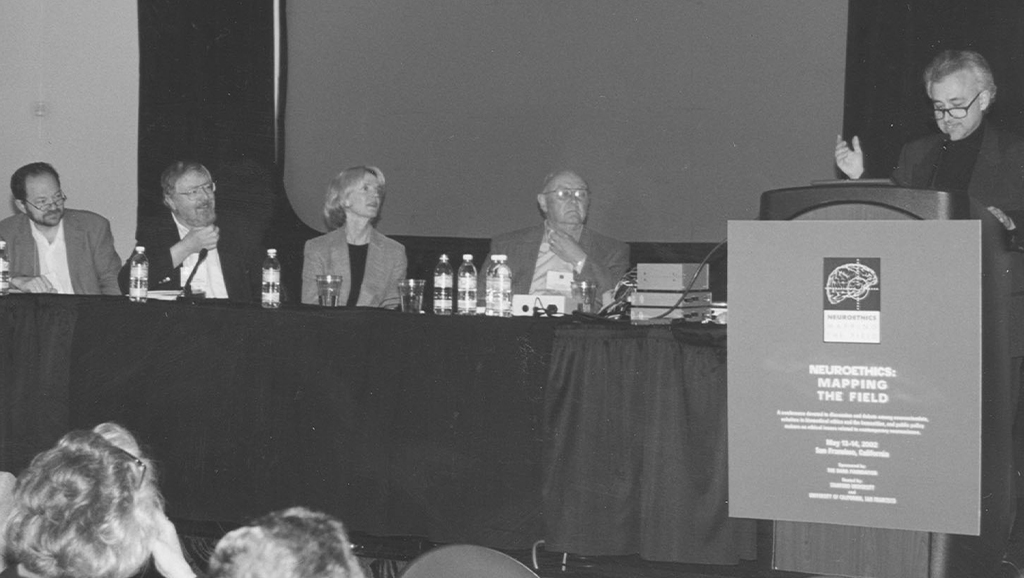

The push for open and sustained dialogue around the ethics of brain science coalesced in 2002, when the Dana Foundation orchestrated a landmark event: “Neuroethics: Mapping the Field.” More than 150 neuroscientists, bioethicists, psychiatrists, psychologists, philosophers, and legal and policy scholars gathered in San Francisco to “reflect on the broad implications of current and ongoing research on the human brain.”

“Bill Safire recognized pretty early that we were entering a new era of the ability to understand and manipulate the human brain—the seat of our thoughts, our emotions, our self-control,” said Steven Hyman, M.D., who attended the meeting and would later become the first president of the International Neuroethics Society, and then the chairman of the board of the Dana Foundation.

With Safire at the helm, this conference modeled the cross-disciplinary dialogue that would become neuroethics’ trademark. These weren’t merely presentations of findings; the presentations and whole-audience discussions were opportunities to grapple with complex, often contradictory ideas.

“The big takeaway was that this had to be a big tent,” said Hyman. “This would fall apart unless there was a sustained conversation among people who were anchored in different disciplines, including, of course, neuroscience.”

The term “neuroethics” had first been coined by Anneliese Pontius in 1973, and seeds of neuroethics had appeared in scattered academic publications of the 1980s and in UNESCO bioethics committee reports in the mid-1990s. But it was Safire’s prominent use of the word at the conference (and later in his New York Times column) that popularized it. The Dana Foundation’s vision, and Safire’s reach, turned a nascent field into a living, urgent conversation—one that would shape research and ethics for years to come.

Expanding the Conversation

As neuroethics outgrew its infancy, the Dana Foundation proved instrumental in shepherding the field into a vibrant, lasting community. Recognizing that breakthroughs require more than one-off conferences, the Foundation committed to building infrastructure—spaces where conversations could deepen, cross boundaries, and endure.

This vision materialized most powerfully four years later, in 2006, at a Dana-backed gathering in Asilomar, California. There, a circle of leading thinkers decided to found the Neuroethics Society (later the International Neuroethics Society).

“We saw the need for a platform to facilitate the kinds of sustained conversations that launch new fields,” Hyman later recalled. Dana’s support provided the scaffolding: crucial funding, organizational backing, and an inclusive spirit that drew lawyers, philosophers, engineers, social scientists, and neuroscientists into the same conversation.

From left: Erik Parens, Marilyn Albert, Steven Hyman, and Bernard Lo at Neuroethics: Mapping the Field. May 13-14, 2002.

Interdisciplinarity wasn’t just a buzzword; it was the engine of progress. “We really did have to invent a new interdisciplinary approach,” Hyman said—one that reached beyond bioethics to ask how law, philosophy, and even computer science must adapt as brain technologies evolve.

The Neuroethics Society swiftly became the nerve center of neuroethics, hosting conferences and debates that tackled the field’s most urgent questions. How should informed consent work for people with cognitive impairments or mental illness? Where do we draw the line when it comes to collecting or sharing neural data? Should cognitive enhancement become a standard tool for self-improvement, or does it threaten our fundamental humanity? The Society’s gatherings, fueled by the Dana Foundation’s sustained investment, created a space for rigorous, sometimes uncomfortable dialogue about the ethical boundaries of brain research.

By bolstering the Society and nurturing this intellectual infrastructure, the Foundation helped give neuroethics a permanent home—one capacious enough to confront new ethical frontiers as neuroscience continues its rapid advance. But even as the community of scholars and professionals deepened its inquiry, Dana recognized that true progress required a broader, more inclusive conversation. The next stage was clear: taking neuroethics beyond the academy and into the public square.

Bringing Neuroethics to Everyone: The Broadcast Years

For much of the 2000s and into the 2010s, the Dana Foundation redoubled its efforts to bring the unfolding story of the brain—and its ethical dilemmas—to a wider audience through ambitious outreach: glossy publications, lively web stories and interviews, public lectures and debates, and regular features in Dana’s flagship publication, Cerebrum magazine.

Events like the “Staying Sharp” series brought brain science and ethical issues directly to community centers and libraries across the country. The Foundation also introduced neuroethics content into its annual Brain Awareness Week campaign, sharing activities and lecture topics to expand the reach of these conversations each spring to schools, museums, and local partners worldwide.

Much of this outreach was top-down, as the Foundation and invited experts curated the latest findings and big questions for public consumption. But this stage played a vital role in “catching up the publics” on the rapid progress and rising stakes of neuroscience. It also helped lay the groundwork for a more participatory kind of engagement that was just around the corner.

Walking the Walk: Neuroscience and Society

With the foundations of neuroethics firmly established, the Dana Foundation recognized the next challenge: making neuroscience a shared project, shaped not only by scholars and policymakers but by the lived realities and values of everyday people.

One of the earliest of these public-facing commitments was the Barbara Gill Civic Science Fellowship, hosted at Arizona State University’s National Informal STEM Education Network (NISE Net). The fellowship set out to “develop new approaches for public engagement with the ethical and societal impacts of neuroscience.”

“We want to show that the scientific community has as much to learn from the public as the public has to learn from the scientists,” said Claire Weichselbaum, the Civic Science Fellow. Her inventive tools—like the Neuro Futures Card Game and the What Makes Us Human game—shifted learning from passive to participatory, encouraging empathy, critical thinking, and deeper understanding of how neuroscience touches real lives.

Dana also backed a pilot program at Columbia University’s Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, focusing on middle school teachers—a “sweet spot” for bridging science and society.

Neuroethics Teachers Institute workshop hosted by Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute.

“Making connections between neuroscience and society is really important for young people, who are interacting with a lot of these technologies and whose brains are developing during their middle school years,” said Maia Gumnit, a public programs manager. Instead of reaching only students, the team amplified their impact by equipping teachers to facilitate complex conversations. The result: “My students used to see science as separate from ethics—just facts and experiments,” reported one middle school teacher who participated in the institute. “Now they debate the implications of technologies they read about, questioning not just whether we can develop them, but whether we should.”

In another innovative approach, neuroethicist Anna Wexler of the University of Pennsylvania piloted a Dana-supported project embedding an ethicist within a neurotechnology startup. Frustrated by ethics panels that ended in talk but no action and aware that many perceive ethics as simply compliance or mere regulatory barriers, Wexler sought “genuine collaboration and mutually beneficial work,” where an ethicist and engineers could co-create projects and confront real problems together. Wexler’s postdoc, Juhi Farooqui, brought both neural engineering expertise and neuroethics insight to a Houston startup, Motif Neurotech.

“Openness was obviously a key quality,” Farooqui said. “The partner had to be open to the collaboration, to the presence of the embedded ethicist in company activities, and to the publication of both the research project and the reflection piece.” The real success, she notes, will lie in whether this model leads not just to published research, but to “concretely influencing the company’s development and commercialization activities”—and, ideally, in whether it provides a replicable roadmap for others to follow.

Neuroethics 2025 was held in April at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences in Munich, Germany.

By championing empathy, reflexivity, and inclusion, the Foundation is ensuring that ethical neuroscience is not the preserve of a select few, but a collaborative, evolving project rooted in the needs and hopes of communities themselves.

“One of the misconceptions I frequently encounter is the idea that the ethical dimension of science primarily revolves around ‘compliance’ or ‘regulation’—something that might impede innovation,” said Caroline Montojo, Dana’s current president. “Our approach, in contrast, focuses on that essential ‘meaty middle’: the practical, meaningful interaction between neuroscience, ethics, and society. Rather than being a brake, ethics is what allows neuroscience innovations to move forward in ways people trust.”

From Dialogue to Design

Neuroethics is now woven into the fabric of Dana’s Neuroscience & Society mission. Nowhere is this more visible than in the Dana Center Initiative, a nearly $20 million commitment to making community engagement, interdisciplinary research, and social impact foundational to brain science.

Each Center Initiative site demonstrates what it means to merge neuroscience with society from the ground up:

- UCLA–Charles R. Drew University Dana Center for Neuroscience and Society (Los Angeles): Partners neuroscientists with community organizations in South Los Angeles to co-create research, train a new generation of leaders, and focus on questions that matter most to local residents. Through seed grants, human-centered design workshops, and public idea salons, the Center empowers both scientists and communities to shape the research agenda together. “Our hope is that, eventually, neuroscience and society will be synonymous with neuroscience,” said the project’s co-director Ashley Feinsinger.

- Neurotech Justice Accelerator at Mass General Brigham (Boston): Brings together health practitioners, scholars, trainees, and affected communities to advance the cause of ethical, equitable neurotechnology through training, advocacy, and convenings such as the annual Neurotech Justice Summit.

- Loyola University Chicago Program in Neuroscience and Society: Uses neuroethics education to connect STEM disciplines with social awareness, especially for pre-college students who are historically underrepresented in science. Loyola’s project aims to infuse neuroscience identity with a sense of social mission and belonging—showing young people that science is as much about serving society as it is about discovery.

“Dana is the only funder that focuses exclusively on this intersection of neuroscience and society,” said Khara Ramos, Dana’s Vice President of Neuroscience & Society. “We would love to see a day where other funders invest even a small portion in these broader issues—but right now, that’s rare.”

Panel discussion from the Science Philanthropy Alliance meeting in New York. May 2024.

Dana’s new model is built around ongoing, deep listening to the communities science aims to serve. “We want to incorporate the things we learn into what we actually do,” Ramos said. “We believe that by listening and understanding various viewpoints with humility and respect, we can collectively shape a brighter future.”

As neuroscience rushes toward new dilemmas—over brain data privacy, cognitive enhancement, the role of AI in health and society, and more—the Dana Foundation’s leadership in funding dialogue, not just research, remains vital. By making public engagement, equity, and ethics fundamental to science itself, the Foundation has set a new standard for how discovery can serve the common good.

Ultimately, the future of neuroscience—and its ability to improve lives—will hinge not just on scientific discovery, but on our collective willingness to ask honest questions, embrace a wide range of voices, and treat ethics not as the brake, but the engine of progress.