Impact Story

From Broadcast to Belonging: Dana’s Public Engagement Evolution

In South Los Angeles, the helicopters come at night. And in the morning. And during homework time. Parents organizing with Esperanza Community Housing had documented it for years—the LAPD and sheriff’s patrol helicopters that hovered longer, and flew lower, over their neighborhoods than anywhere else in the city.

In 2023, they had the chance to actually ask a neuroscientist: What is this doing to our children’s brains?

When researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and Charles R. Drew University (CDU) of Medicine and Science arrived at community listening sessions that year, they came to listen, not lecture. The sessions, conducted in Spanish and English, revealed a web of environmental stressors: noise, heat, air quality, all intersecting in ways that traditional neuroscience research had rarely examined. The helicopter noise stood out—concrete, measurable, addressable.

This wasn’t how neuroscience typically worked. But the newly formed UCLA-CDU Dana Center for Neuroscience & Society project had a different model: Let communities identify the questions that matter to them. Use neuroscience to find answers. Push for change together.

This approach marks the latest evolution in the Dana Foundation’s 30-year journey with public engagement. To understand how radical this shift is, you have to go back to a November day in 1992, when neuroscience’s relationship with the public was about to change.

A Marketer Among the Scientists

Barbara Gill had been on the job leading public affairs at the Dana Foundation for barely three months when David Mahoney, the Foundation’s chairman and a former top marketing executive, invited her to go with him to a meeting at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

More than thirty of the world’s leading neuroscientists and heads of federal agencies and private foundations that sponsored brain research had convened to discuss a challenge: Despite President George H. W. Bush declaring the 1990s the “Decade of the Brain,” federal funding wasn’t following. The scientists spent hours presenting their research, each making their case through formal academic presentations.

Barbara Gill (center) leading a discussion with the Dana Alliance.

“David turned to me,” Gill recalls.” He said, ‘They’re not selling me on anything.’”

In the middle of the meeting, Mahoney stood up. He described how awareness campaigns for AIDS research and for breast cancer awareness had brought attention and funding to those causes. Neuroscience needed to make some noise.

“If you’re willing to step out of your labs and talk to the public,” he said, “I will create a platform for you, and I will fund it.”

The scientists said yes.

Within a year, the Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives was born, with 80 scientists, including Nobel laureates and other leading researchers, committing to something that had been almost taboo—talking to nonscientists about their work.

“People don’t buy research,” Mahoney would later tell the New York Times. “They buy hope. What people care about is the health of their family and their community.”

Building the Movement

The Alliance’s first test came at Southampton College, with a forum on genetics and neuroscience. Despite worries that the topic was too specialized, the room filled beyond capacity. “We literally had to cut off questions,” Gill says. “It would have kept going for hours.”

By 1995, Mahoney was restless for something bigger. “He came in one morning asking if we knew what day it was,” Gill remembers. “None of us did. Turns out it was Prostate Cancer Awareness Day. That’s when he decided the brain needed its own week.”

One week each year when neuroscientists worldwide would simultaneously engage their communities. Local events shaped by local interests. A lab might host hands-on demonstrations for kids. A university might organize cafe discussions about memory. Schools could run brain fairs in village squares.

Brain Awareness Week launched in March 1996 with 160 participating US organizations. By year three, the campaign had spread to six continents.

“The goal wasn’t just education,” Gill says. “It was showing people they had a personal stake in brain research, whether that meant hope for treating Alzheimer’s, understanding addiction, or helping their kids learn better.”

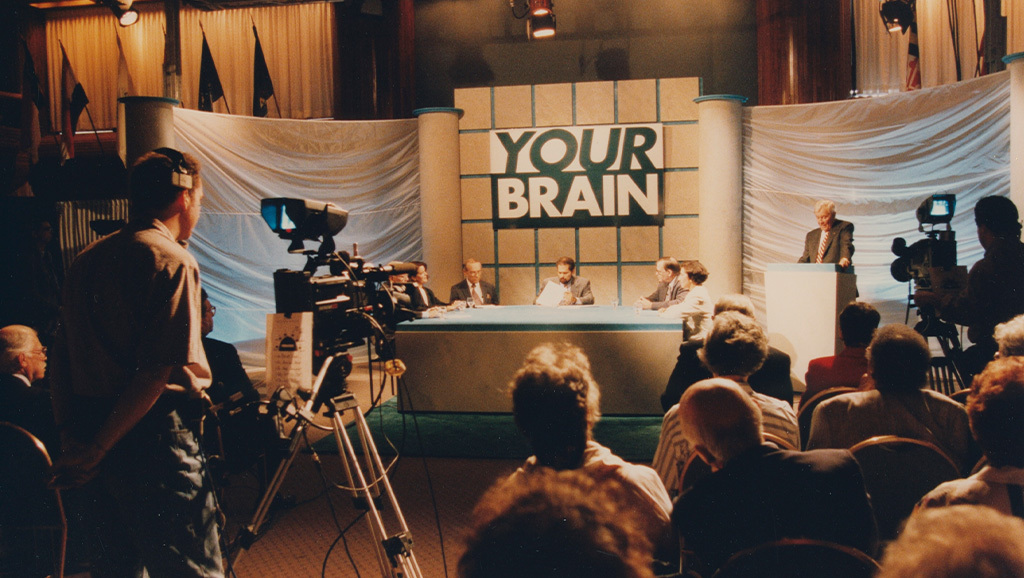

A past Brain Awareness Week fair at Vanderbilt University.

Beyond grassroots events, Dana publications spread the word wide. BrainWork, a free mailed newsletter, translated neuroscience breakthroughs into plain English—and eventually reached 33,000 subscribers. The quarterly journal Cerebrum explored deeper implications in essays. “One was telling people what’s out there, the other was intellectual—fascinating articles,” Gill says.

By 2000, the Foundation had proven the public hungered for quality neuroscience information.

Enter the Wordsmith

When William Safire took over as Dana’s chairman in 2000, he inherited a foundation already deep into science communication, reaching tens of thousands through quality publications. But the New York Times columnist saw a new challenge emerging: The internet was democratizing access to health information but also flooding the public with unverified claims and pseudoscience. Where Mahoney had focused on generating enthusiasm for brain research, Safire emphasized verification and quality control, understanding that misinformation about the brain could have profound ethical consequences for how societies treat mental illness, addiction, and consciousness itself.

Safire championed neuroethics before it was even a formal field, and created the Dana Press division to publish books that took communications beyond newsletters and into bookstores. Jane Nevins, hired as editor of the Press, remembers Safire’s exacting standards: “He wanted books that were scientifically impeccable but readable on an airplane.”

Dana Press published roughly 30 titles over the next decade—from practical guides like Keep Your Brain Young to unexpected collaborations like The Bard on the Brain, which explored neuroscience through Shakespeare’s plays.

When Edward Rover took the helm in 2009, he connected neuroscience to law through judicial education, recognizing that judges increasingly needed to evaluate brain science in their courtrooms. Each leader anticipated what the field would need next. Brain Awareness Week expanded to 120 countries. Congressional briefings explained everything from adolescent brain development to military traumatic brain injury.

By the 2010s, the Foundation had succeeded in making public engagement common practice in neuroscience. “Young scientists were out there doing their programs,” Gill says. “They felt that was part of who they were and what their job was as a scientist.”

The question then became: What next?

The Participatory Turn

By 2018, the limits of the broadcast model were becoming clear. Dana could publish excellent books, but who was reading them? They could organize forums, but were they reaching beyond the already-interested? Most fundamentally: Were communities actually benefiting from all this neuroscience knowledge?

The board, led by Steven Hyman—one of neuroethics’ founders—began asking different questions. Instead of “How do we tell people about neuroscience?” they asked, “How can neuroscience serve society’s needs?” The answer had grown urgent as the field matured.

“Neuroscience now has tools that can directly affect people’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors,” says Caroline Montojo, current president of the Dana Foundation, who arrived from the Kavli Foundation in 2021. “With neurotechnology like brain-computer interfaces, this brings questions like: Who owns brain data? Where do we draw the lines between therapy and enhancement? These are societal questions that can’t be answered by scientists alone.”

Having previously worked with the NISE Network on neuroscience and society engagement while at Kavli, Montojo brought experience with participatory science models that would reshape Dana’s direction. The Foundation’s first grant under her leadership signaled the shift: The Barbara Gill Civic Science Fellowship, named for Dana’s longtime executive who had shepherded public engagement from Mahoney through Safire and Rover. The fellowship embodied the bridge between eras—honoring the Foundation’s broadcast legacy while pioneering participatory approaches.

Claire Weichselbaum, who received the fellowship, developed tools that flip the traditional dynamic. The card game “Neuro Futures” invites people to explore neurotechnology from multiple perspectives—patient, caregiver, ethicist, engineer. Another tool asks participants what makes humans uniquely human, then challenges them to design an imaginary robot with those qualities.

“We want to show that the scientific community has as much to learn from the public as the public has to learn from the scientists,” Weichselbaum says.

The results were striking. At the test site, the Arizona Science Center, visitors spent longer with these interactive experiences than with traditional exhibits. More importantly, they reported feeling that their perspectives mattered.

From Subjects to Partners

The shift accelerated with the 2024 launch of the Dana Center Initiative—a $20 million partnership with three institutions pioneering community-partnered neuroscience.

In South Los Angeles, UCLA and CDU researchers took the community’s question seriously.

They didn’t just study the effects of noise—they studied it the way residents experienced it. They recorded actual helicopter noise from South L.A. streets. They exposed fruit flies and rodents to the same sonic patterns that kept children awake. The results confirmed what parents suspected: Chronic noise exposure disrupts brain function.

But here’s where the Foundation’s new public engagement model diverges from the old. Under the broadcast approach, scientists would have published their findings or written an op-ed. Perhaps given a public lecture.

Instead, the UCLA-CDU research team accompanied community members to Los Angeles City Hall. Together, they presented the findings to city council members debating whether to purchase additional law enforcement helicopters. The science gave weight to lived experience. The community gave context to the data.

The UCLA-CDU team on a community visit.

“We are tired of being guinea pigs for different studies,” Monic Uriarte from Esperanza Community Housing told the L.A. Times at the time. “We need this kind of collaboration—a space for our community to share, in our own words, the experience of living in South Los Angeles.”

The vision became real for Montojo during a Zoom meeting when the UCLA-CDU team presented their experiences during a proposal evaluation. “They walked us through their entire model—from community listening sessions to research question to City Hall. Our Dana staff all looked at each other and said, ‘This is exactly what we had hoped for.’”

A New Generation

This participatory approach fuels Dana’s three grant “pillars.” Dana’s Education program supports innovative neuroscience education for all ages—strengthening understanding of the brain’s relevance to daily life, inspiring K–12 students to consider neuroscience careers, and helping professionals apply neuroscience in their work. Dana’s NextGen program prepares emerging scientists to think beyond the lab from Day One through interdisciplinary training. Dana Frontiers funds projects that bring together scientists and communities to connect neuroscience to people’s real needs and opportunities—building trust, sharing knowledge, and creating new ways for peoples to shape and benefit from neuroscience.

“It’s about demonstrating trustworthiness,” says Devon Collins, director of the Frontiers program. “Approaching people from a position of, ‘I may have something to offer given my domain expertise, but you are an expert in your own life.’”

For example, with Dana support, The Chicago Council on Science and Technology partnered with West and South Side communities to co-design brain health events. Instead of lectures about neuroscience, they created “Brain Garden” gatherings in local parks with food experiments and art. “Mind Matters” workshops at community centers focused on what residents actually wanted to know about: stress, sleep, and mental health.

“People of color have always kept things inside their homes, inside their hearts, and they suffer in silence,” says Star Braddock, a community outreach associate at The Encompassing Center who helped shape these events. “We share our passion about mental health and tear down barriers and stigmas.”

Four years into its redirection, the Dana Foundation is now entering its evaluation phase, measuring not traditional metrics but trustworthiness itself. Do communities see researchers as partners rather than extractors? Are research priorities shaped by community needs? For Montojo, success means “a neuroscience field that is both scientifically strong and socially responsive.”

Who Shapes Tomorrow

Those helicopters still fly over South L.A. But now, when the city council debates purchasing more, community members arrive equipped, armed with data about how they affect children’s brains. Neither science nor storytelling alone could achieve change. Together, they become undeniable.

This is the goal, says Montojo: “Neuroscience and society becoming recognized as a research paradigm—not just interdisciplinary collaboration, but a fundamental way of doing research.”

Today’s eight-year-olds will graduate college in 2045. By then, brain-computer interfaces may be as common as smartphones. Neural enhancement could reshape education. AI trained on brain data might predict mental health crises before they occur. The question isn’t whether these technologies will exist—it’s who will shape them.

“We’re in a new context where neuroscience is in a renaissance,” Montojo says. “Many aspects that were dreams, even science fiction, are now reality. We have to shift from a dissemination model to a true participation model to incorporate the voices of many to shape the future of the field.”

What Mahoney started when he declared, “They’re not selling me on anything,” what Safire formalized through neuroethics, what Rover expanded through judicial education—all built toward this moment. Each leader anticipated what neuroscience would need next and helped set the groundwork for what’s happening now. “We couldn’t do what we do today if we didn’t do all this before,” says Barbara Gill.

The Foundation that once taught people about the brain now helps communities shape what brain science becomes. Trust isn’t built through one-way communication. It emerges when communities see their concerns reflected in research priorities, their values embedded in technology design, their voices included from the start.

Recommended Reading

Reciprocity in Neuroscience: Dana Foundation Panel at the UN Science Summit

Trust and Engagement in Neuroscience: Listening Must Shape the Future